STARRY WISDOM

Necrononomicon Part IV: Initiation, Alien Contact, and the Esoteric Vision of Peter Levenda

In our first entry, Black Stars in Dim Carcosa, we opened the gates to a twilight realm of cosmic mystery, drawing inspiration from the haunting whispers of Carcosa. Next, Dreamers in the Void carried us deeper, exploring how dreams and visions bridge our reality with the vast Other beyond the stars. More recently, Tentacled Aeons confronted us with the monstrous sublime – those ancient, tentacled forces that lurk at the edges of time and sanity.

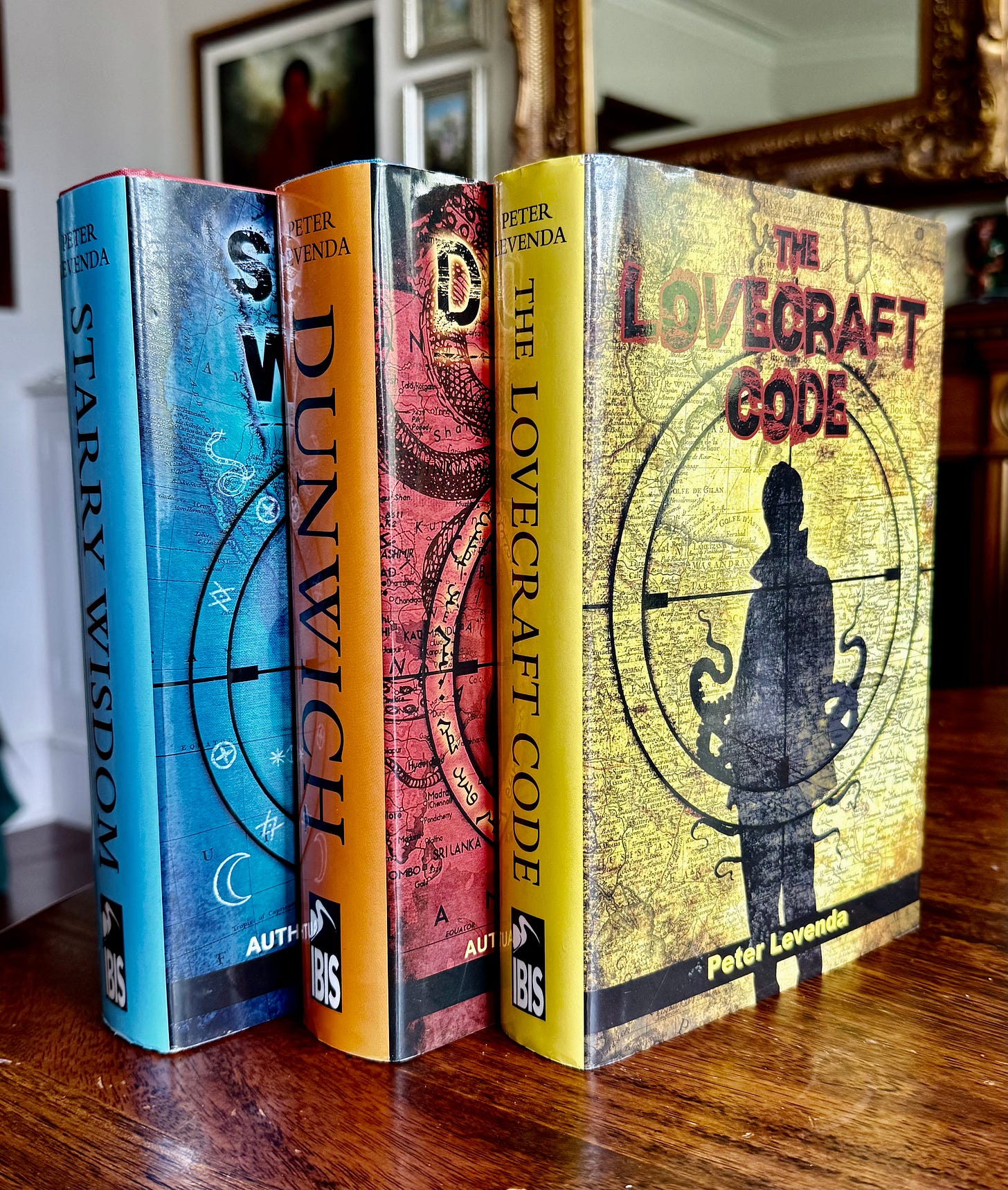

Now, in this fourth instalment, we turn our focus to a contemporary work that ties all these threads together: Peter Levenda’s Lovecraft Trilogy, particularly the novels Dunwich and Starry Wisdom. Under the guise of fiction, Levenda weaves esoteric truths about initiation, contact with alien powers, and the transformative power of fear. In doing so, he has crafted a kind of fictional grimorium, a grimoire in novel form, that resonates strongly with the Mythos magick theme of our series. As we shall see, Levenda’s work not only pays homage to H.P. Lovecraft’s imagination but also serves as an initiatory journey for both his protagonist and the reader.

And with

himself soon appearing as a guest in our Black Stars in Dim Carcosa course, it’s the perfect time to delve into the Starry Wisdom hidden in his pages – and to see why facing one’s deepest fears can be the doorway to awakening.Before we proceed, a word of caution: this article contains major spoilers for The Lovecraft Trilogy, especially the novels Dunwich and Starry Wisdom. If you have not yet read these books and wish to experience their revelations firsthand, you may want to pause here and return once you’ve journeyed through Levenda’s eldritch landscape. What follows is an esoteric exegesis—one that will unveil key moments, character arcs, and hidden initiatory truths embedded in the narrative. You have been warned.

The Fictional Grimoire You Were Meant to Read

Peter Levenda is no ordinary novelist. He is an occult scholar and historian by trade, known for his scholarly works on secret societies and dark religions. Many of you may recall Unholy Alliance, his famous study of Nazi occultism.

But Levenda also has a clandestine pedigree in the world of Mythos magick: he has long been rumoured to be “Simon,” the mysterious author of the Simon Necronomicon. If Alan Cabal and the U.S. Copyright Office are to be believed, Levenda was intimately involved in that project. In other words, he’s a master of blurring the line between occult truth and literary invention. Little wonder, then, that when he turned to writing fiction, the result was fiction drenched in fact, novels that hide genuine occult teachings behind plot and character.

Levenda’s Lovecraft Trilogy consists of The Lovecraft Code (2016), Dunwich (2018), and Starry Wisdom (2019). These novels form a continuous story that takes Lovecraftian lore and grafts it onto the modern world of espionage, religion, and secret societies. In these works, Levenda presents real occult concepts – initiation rituals, incantations, spiritual entities – under the guise of a high-speed thriller plot. It’s a wild ride: Dunwich, for instance, begins with an alien abduction in rural New England and spirals outward to include a renowned mathematician, mercenary geneticists, an international ring of pornographers, the human-trafficking cult of ISIS, and practitioners of arcane sexual occultism. All of these disparate threads connect to a shocking secret in an ancient book of magic – yes, essentially the Necronomicon – a secret so potent that unlocking it will cause ancient, submerged temples to rise again from the sea. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror meets real-world conspiracy and spiritual warfare.

Such an ambitious mélange works because Levenda brings to it the rigour of a researcher and the passion of an occultist. Reviewers have noted that his breadth of knowledge and attention to detail make even the strangest events feel plausible.

Indeed, Levenda’s background in occult history is evident at every turn – he peppers the novels with authentic esoteric lore, from Sumerian mythology and tantric ritual to quantum physics and modern political intrigue. In these novels, he connects Lovecraft’s mythos to everything from Middle Eastern religious conflict to cutting-edge science. The result is a story that operates on two levels. On the surface, it’s a globe-trotting thriller that could out-Dan Brown Dan Brown. But beneath that, for those with eyes to see, it’s a treasure trove of occult insights. In a way, the Lovecraft Trilogy functions like the fictional Necronomicon within it: delivering hidden truths under the guise of fiction, just as the Necronomicon conveys ancient truths under the guise of myth.

Levenda’s protagonist in the trilogy is Gregory Angell, a professor of religious studies – and notably, a namesake of Lovecraft’s Professor Angell (from “The Call of Cthulhu”). This is no coincidence. Gregory Angell is our stand-in, the scholarly seeker drawn into dangers he only thought he understood from books. Through Angell’s journey, Levenda explores three key themes that we will focus on: initiation, contact with the alien Other, and fear as a catalyst for transformation.

We will delve into each of these in turn, examining key scenes and characters – including the enigmatic Lara Kidul – to see how Levenda’s fiction reflects genuine occult principles. As we proceed, keep in mind that Levenda’s work is deeply in conversation with the previous topics we’ve discussed. The black stars over Carcosa, the dreamers in the void, the tentacled aeons of primordial time – all find echoes in the Lovecraft Trilogy. By the end, you may find that reading these novels is itself a kind of initiation. And with Peter Levenda set to join us in the upcoming course, we will have the opportunity to confirm just how much of these esoteric layers he intended (perhaps all of it, and more).

The Initiatory Journey: From Scholar to Seeker to Adept

Initiation – the passage from the known into the unknown, through trial and revelation – lies at the heart of Levenda’s trilogy.

Gregory Angell’s arc is, in essence, an initiation narrative. When we first meet Angell (in The Lovecraft Code), he is a man of reason and academia, perhaps a bit world-weary but not yet a true believer in the supernatural. That changes quickly. Levenda wastes no time in subjecting his protagonist to ordeals that shatter his ordinary worldview. Early in the saga, Angell is sent on a mission by shadowy government handlers to investigate strange happenings in the Middle East. This leads him to witness a massacre of Yezidi workers by ISIS militants – a profoundly traumatic human evil that leaves him spiritually devastated: “the massacre… made Angell lose his faith in God forever.”

Here is the first step of initiation: the death of the old faith. Angell’s comfortable assumptions are burned away in a crucible of horror and disgust. In classical initiatory alchemical terms, this is the Nigredo, the blackening – the stage of putrefaction where one’s former beliefs decompose.

Many initiatory myths and rites begin with the candidate’s separation from their old life and a confrontation with death or despair. Angell’s loss of faith is exactly that. After seeing innocents slaughtered in Mosul, he can no longer cling to any naive religious conviction. He has gazed into the heart of human darkness and found a void.

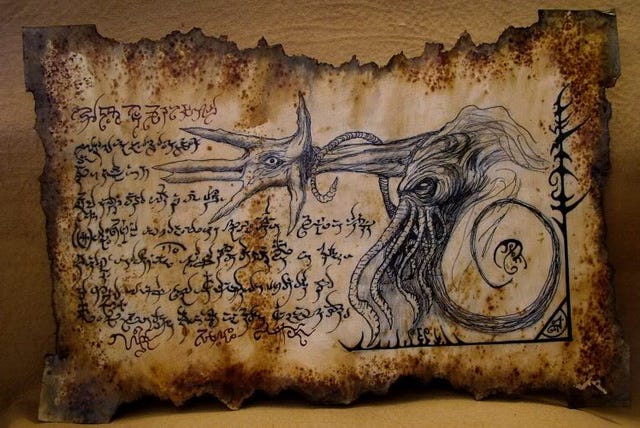

But the initiation has only begun. From the ashes of Angell’s faith, a new quest arises: the search for a book. Specifically, Angell learns of a mysterious tome – Al Azif, known in Greek as the Necronomicon – which various powerful groups are desperate to obtain. His handlers all but throw him into the deep end: find the book, whatever it takes. Angell’s pursuit of this “black book of the Dagon cult” becomes the thread that pulls him through a labyrinth of secret orders and dangerous encounters.

Every step he takes is a deeper descent. In Turkey, at a refugee camp, he encounters a young Yezidi woman seemingly possessed by a demon. In a hidden monastery in Nepal, beneath a Himalayan mountain, he witnesses a ritual that goes terribly awry – the girl appears again, now as the vessel for an unspeakable entity.

“The entire room began to tremble with the force of something that he could not name… except through the book that she held.”

That book, of course, is the Necronomicon, and something is using the girl to manifest. Angell watches in dread as her voice and even her face begin to transform into something inhuman.

The ritual reaches a crescendo of terror:

“The force of that experience – the sensation that something unbelievably evil was rising up from the bowels of the Earth to threaten the world – was enough to shatter his atheism.”

In that Nepal cave, Gregory Angell comes face to face with the reality of the Mythos. It is no longer academic theory or mythic symbolism – it is happening, palpably and horrifically, before his very eyes. In Lovecraftian terms, Angell has read the forbidden book and now confronts the daemon sultan himself; in occult terms, the initiate has undergone the Ordeal.

At this point, many a Lovecraft protagonist would lose his mind or life. Angell nearly does. He “fled the scene with the accursed book”, shaken to his core, sanity hanging by a thread. The old professor is effectively dead – he’s now a fugitive, a guardian of a dreadful grimoire, and a man who knows for certain that cosmic horrors are real. This is initiation by immersion. Angell’s ignorance has been slain, but he hasn’t yet been reborn; he is in that liminal state of crisis.

Fittingly, he spends a period in the wilderness, fleeing through Afghanistan, Iran, and China, ultimately finding a hideout in Indonesia. During these wanderings, he has time to study the Necronomicon and piece together why so many factions want it. He realises the text is “the survival of an ancient Mesopotamian tradition of magic and spiritual manipulation”, often confused with the Yezidis’ own legends. In other words, Angell comes to see that the Necronomicon is real, not a mere invention of a mad Arab, but a lineage of sorcery reaching back to Sumer and beyond. This revelation bridges his scholarly knowledge with the terrifying new reality he’s witnessed. We might say he’s assembling a new worldview, integrating the fragments of truth he’s acquired at great cost

The culmination of Angell’s initiation occurs on a lonely beach in Java. Here, having evaded death so far, he performs (or is at least a participant in) a shamanic ritual with a local dukun (shaman) and the Necronomicon itself. What happens on that beach is the epiphany that completes his transformation. In a midnight rite by the roaring surf, Angell experiences a vision of Lara Kidul, the goddess of the Southern Ocean revered in Javanese mysticism.

Lara Kidul – sometimes called Nyai Loro Kidul – is a spirit queen, the mythical bride of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, and a protector of Java’s people. To Angell’s eyes, she rises from the waves in majesty. At the same time, he becomes aware of another presence at his back: “behind him had stood none other than the Kutulu of the Necronomicon, the Cthulhu of Lovecraft.”

In this moment, Levenda draws a stunning parallel – the Goddess and the Great Old One, face to face. Angell stands between a divine figure of local tradition and a cosmic horror of global fiction, and he understands they are connected.

“In that shamanic ritual on the beach, the Goddess and the Old One were like particle and wave, two forms of a central premise that could not be embraced or identified until one was destroyed and the other survived.”

Here Levenda slips an esoteric truth into poetic imagery: he implies that these two entities are dual aspects of one reality, like the dual nature of light in quantum physics. One is nurturing, one is destructive; one “particle,” one “wave” – yet ultimately they are the same phenomenon viewed differently. The initiate (Angell) perceives this higher unity only in a moment of intense vision.

This beach ritual is Angell’s initiation consummation. It is terrifying, awe-inspiring, and illuminating all at once.

Lara Kidul, as a manifestation of the Divine Feminine or Mother Sea, does not destroy Angell; she blesses him – though it’s a fierce blessing. Angell feels “frightened by the Goddess, but protected by her”. The text describes how “an alien Goddess blessed him with her severity”, pushing him to the brink of breakdown, yet giving a boon in the process.

n mystical terms, this is initiation through ordeal. Angell’s psyche is almost torn apart by the encounter, “falling apart… on the verge of a mental breakdown”, but simultaneously he senses himself “coming together, on the verge of a mental breakthrough.” The old self dies; a new self is born. After surviving this night, Angell is no longer the same man who fled that cave in terror. The Javanese shaman, Pak Mahmoud, looks into Angell’s eyes afterward and immediately sees the change: “The Goddess of the Southern Ocean had blessed him. He need fear no longer.”. Fear no longer – what a phrase! It rings like the pronouncement at the end of an initiation ceremony, when the initiate is told he has conquered the ordeals and is now one of the elect. Angell has faced death and cosmic madness, and lived. Like a shaman who has been to the underworld and returned, or a mystic who has passed through the Dark Night of the Soul, he emerges empowered. The narrative explicitly notes his transformation: after these events, “he was less cynical, less pessimistic… He felt empowered in a way that he never had before.”

The journey that began with despair in Mosul ends in a kind of gnosis in Java. This is initiation – painful, costly, but ultimately life-altering in a positive way.

As readers, following Angell’s path is meant to be initiatory as well. Levenda structures the novels so that we experience the confusion, dread, and revelation alongside the protagonist. By the time we reach that beach in Java, we too have been exposed to a barrage of arcane ideas and horrific imagery, then given a moment of almost transcendent synthesis. There is a distinct feeling that Angell’s breakthrough is also a message to us: persevere through the fear, and you will be rewarded with insight. We discussed Carcosa in previous instalments as a place where one might lose oneself to find truth – Gregory Angell essentially had his Carcosa moment and emerged the other side, initiated.

Contact with the Alien Other: Gods, Monsters, and the In-Between

One of the central fascinations of Lovecraft’s mythos, and occult practice, is the idea of encountering the Other – that is, meeting intelligences or beings that are not human.

Whether we call them gods, spirits, aliens, or Great Old Ones, the urge to make contact with non-human power runs through both fiction and esoteric lore. Levenda’s novels are rife with such contacts. In fact, every major movement in the trilogy involves a brush with some “Other” – sometimes malign, sometimes beneficent, often ambiguous.

Let’s look at a few of these encounters:

The Yezidi girl’s possession in Nepal, where an entity (eventually identified as Cthulhu/Kutulu) speaks and acts through her, is a clear instance of contact. In that scene, Angell and others hear a voice proclaiming blasphemies in a mix of languages. “Before Iblis and Lucifer, I am… Before all the gods you worship, I am… There is no god where I am. I am the headless corpse, the faceless bride of darkness…” the thing declares, in a terrifying tirade. Angell realises with horror that the being speaking is not truly the girl at all – it is using her as a mask, a “reasonable fiction of a man” (or rather, of a human) to appear in this world. This is a classic evocation gone wrong scenario, reminiscent of both demonic possession and Lovecraftian avatar manifestations. The “alien Other” in this case is outright hostile and predatory, describing itself as the patron of war and cruelty (the speech references jihadi atrocities, claiming “They call on God, but find me instead”). It’s as if a demon or ancient god revealed its true face under the veneer of religious violence. The contact leaves everyone shaken – and the reader, too, feels the intensity. Levenda isn’t just writing a spook story; he’s hinting at a profound idea: that inhuman forces move through human agents in our world, whether we recognise them or not. From an occult perspective, this isn’t far-fetched – many traditions speak of spirits influencing leaders or feeding on conflict. In Levenda’s fictional framework, Cthulhu (or an Old One akin to him) might be one such force, delighting in chaos and carnage.

In contrast, the encounter with Lara Kidul on the beach is an alien contact of a very different flavour. Lara is technically “alien” to Angell – she’s an ancient spirit, not human – yet she appears as a protective, even compassionate presence. She is tied to a local sacred geography (the axis between Mount Merapi volcano and the Indian Ocean), embodying the land’s spiritual power. When Angell sees her emerge from the waves, it is a moment of numinous contact – Rudolf Otto’s mysterium tremendum et fascinans in full effect. He is awestruck and terrified, yet also strangely comforted. Lara is described as having a green colour (in Java, she’s often associated with the colour of the Indian Ocean’s waves), and her severe blessing leaves Angell with newfound courage. Notably, as she appears in front of Angell and Cthulhu looms behind him, Angell is literally positioned between a deity and a demon (or say, an angelic figure and a demonic figure). This simultaneous contact produces a kind of reconciliation of opposites. Levenda’s quantum metaphor – particle and wave – suggests that Lara Kidul and Kutulu (Cthulhu) are a duality, perhaps even a polarity of feminine and masculine aspects of the cosmic unknown. One might even interpret this as the meeting of an archetypal Goddess and an archetypal Dragon. In occult symbolism, the union or integration of these forces will yield enlightenment. Angell’s soul, in that ritual, is the battleground or the alchemical vessel in which this union occurs. Levenda thereby implies a daring idea – that the “gods” of traditional religion and the “gods” of the mythos might be masks of each other. Contact with the Other, then, can come via different masks: some beautiful, some monstrous, all partial glimpses of a greater truth.

Aside from these dramatic supernatural confrontations, Levenda also portrays contact with the alien Other in more subtle ways. For example, Dunwich opens with an alien abductee in New England. This is a nod to the UFO lore of our real world – the so-called “Greys” and mysterious kidnappings in the night – but by invoking it in a Lovecraftian context, Levenda hints that such modern extraterrestrial encounters might be part of the same continuum as ancient demonology. Could Lovecraft’s “aliens” (like the Fungi from Yuggoth or the Old Ones) be behind UFO abductions? The novel seems to invite that speculation. Later, Angell crosses paths with a renowned mathematician and other scientists, suggesting that communication with the Other could come through mathematical codes or genetic experiments. In fact, Dunwich features “mercenary geneticists” and occult sex practitioners working hand in hand – a disturbing cabal trying to breed or invoke something inhuman. Here again we see a form of contact: the attempt to create human-alien hybrids, or to use the human body as a gateway for alien entities (a theme Lovecraft himself explored with the Whateleys in The Dunwich Horror). Levenda takes that premise and runs with it on a global scale. The secretive organisations in his story engage in planned contact: orchestrated rituals, coordinated atrocities, all designed to let the Outside in. This is Mythos magick pure and simple – exactly what our course title suggests. The frightening ritual at the climax of Dunwich is a prime example: cultists of Dagon and sinister pornographers come together in a grotesque ceremony of sex magic intended to tear open a portal. And it works – contact is made. “They had made contact with the sunken city, the beyul of Kutulu, the Shambhala of Shaitan. The High Priest himself had torn the membrane between this world and his.” In a single sentence, Levenda links Lovecraft’s R’lyeh (the sunken city) with a Tibetan concept of a hidden spiritual sanctuary (beyul) and the Islamic notion of Shaitan’s paradise (or perhaps an anti-paradise). This syncretism is breathtaking: it suggests that the undersea home of Cthulhu is analogous to Shambhala, the mythical hidden land of enlightenment – except in an inverted way, as Shambhala of Shaitan. The alien Other, in this contact, is framed in many languages and traditions at once.

The recurring motif in all these encounters is that contact with the Other is double-edged. It can destroy, illuminate, or both.

This theme of peril and potential mirrors many accounts from occult and mystical literature. Consider the shamanic initiation: the shaman candidate often meets a terrifying spirit or undergoes a dismemberment vision, and if they survive, they gain healing powers. Or the ceremonial magician’s evocation: if properly prepared, he may converse with the spirit and gain wisdom, but if things go wrong, obsession or death may follow. Levenda clearly knows these parallels, and he bakes them into the narrative. The difference between a catastrophic contact and a constructive contact in these novels often hinges on intention and context. The ISIS cultists and evil magicians seek contact for power and chaos; they get consumed by what they call up (several meet grisly ends at the tentacles of what they summon). Angell, on the other hand, stumbles into contact as a seeker – he has a purity of inquiry, or at least a willingness to learn and a kind of courage. Thus, when he contacts the Other, he is transformed rather than annihilated.

Lara Kidul as a character is worth examining more here, because she embodies the idea that the “alien Other” need not be an alien in the sci-fi sense, but simply a being beyond our ordinary reality.

In Javanese tradition, she is simultaneously feared and revered. Locals say you shouldn’t wear green on her beach or she might take you. She is a threshold being, bridging the human world (as a sometimes-human princess in legends) and the spirit world (as queen of the sea spirits). By incorporating Lara Kidul, Levenda brings a mythic depth to his Lovecraftian tale. He’s effectively saying: Lovecraft’s fictional gods like Cthulhu can be viewed alongside real-world indigenous deities like Kidul. When Angell encounters both, he realises they might be part of one pantheon of the Other. This aligns with certain occult theories; for example, Kenneth Grant wrote about the notion that there is a “Typhonian Tradition” where beings like Cthulhu, Kali, and others are facets of a single current. Levenda doesn’t explicitly mention Grant in the novel, but the resonance is there. By having Lara Kidul and Kutulu appear together, he dramatises the idea that cultures around the world are interacting with the same mysterious forces, albeit under different names and guises.

The title Starry Wisdom itself is a reference to Lovecraft – the Cult of Starry Wisdom appears in his story The Haunter of the Dark, which worships a cosmic entity via a strange shining trapezohedron (a mystical stone). In Levenda’s Starry Wisdom, we can infer that the pursuit of “starry wisdom” is the pursuit of knowledge from the stars – knowledge from alien gods.

Everyone in the novel is after that wisdom in one way or another: the cultists want to unleash star-born horrors, the intelligence agents want the power the Necronomicon might grant, Angell wants understanding, and Lara Kidul (perhaps) wants balance restored. Contact is the means to that wisdom. One must touch the Other to learn from it.

But Levenda also shows that contact has a price. Fear, trauma, and danger are the cost of dealing with gods or demons.

As the old magical adage goes, “Do not call up that which you cannot put down.” Throughout the Lovecraft Trilogy, we see what happens when contact is attempted without proper respect or preparation: madness for some, monstrous infestation for others. The mirror portals in Dunwich’s grand rite, meant to be protective mandalas, instead become gateways spewing horrors. The magicians conducting the ritual are transfixed by the eldritch entities they have summoned – unprepared for the reality of what they have sought. In one striking passage, an “army of the damned” passes through, and even seasoned occultists are left gaping as demonic mutants materialise, struggling to take stable form in our world. These beings are described in grotesque detail – monstrous images of chimaeras, failures of human imagination that can only concoct monsters out of twisted sexual urges and violence. It’s as if the very process of contact is being hindered by the limitations of the human minds present: the entities appear as misshapen, obscene parodies (half horse, half rooster, dripping acid; men with faces in their torsos, etc. – direct visions out of medieval demonology engravings). Levenda suggests that these alien forms are so far beyond our comprehension that they become distorted when forced into our reality, filtered through our psyche’s nightmares. This is a brilliant way of literalising Lovecraft’s famous theme of the incomprehensibility of the Other. The cultists wanted power, but they got a hellish circus that even they couldn’t handle.

By contrast, Angell’s contact on the beach – guided by a traditional shaman and perhaps by his more humble intent – results not in pandemonium but in a moment of clarity (after the terrifying vision). We even see scientific language creep in: he notes a clue to “the problem of gravity and unified field theory” in the flickering image of the shaman possessed by a spirit. This juxtaposition of science and mysticism – photons behaving as particles and waves when the spirit-form appears – reinforces the idea that contact with the Other might hold answers to fundamental mysteries of the universe. Angell can’t work out the physics, but he intuits that some great truth is hidden in that paradox of being (“I am, and I am not,” says the entity in that moment). Contact brings knowledge, if one survives it.

Ultimately, Levenda portrays contact with alien forces as the key to both the horror and the enlightenment in the trilogy. Every initiation requires a meeting with the unknown; every attainment of “starry wisdom” requires reaching beyond the human.

In the context of our broader exploration of Mythos magick, this couldn’t be more appropriate. We’ve talked before about dream-quests and cult invocations – those are all methods of contacting the Other. Levenda’s fiction gives us vivid case studies of how such contact might play out. It invites us to ask: when we seek communion with something beyond the human (be it a god, an angel, an alien intelligence), what do we expect, and how do we prepare? His answer, through Angell’s story, seems to be: expect the unexpected, expect fear and wonder intertwined, and prepare by purifying your intent (or else!).

Fear as the Catalyst of Transformation

“Fear is the mind-killer,” says the famous line from Dune. In the occult traditions, fear is often seen as the gatekeeper of the threshold – the demon guarding the treasure, the Sphinx that poses a deadly riddle.

One must confront and overcome fear to make progress. Peter Levenda deeply understands this dynamic, and he makes fear the engine of his narrative and the crucible that forges his characters’ souls. Time and again in the Lovecraft Trilogy, it is in moments of intense fear that the most significant changes occur.

Gregory Angell’s personal evolution, as outlined, hinges on two major, fear-laden events: the Nepal ritual and the Java ritual. Each pushes him to a breaking point. In Nepal, the fear was existential – this should not be happening, this rips apart my understanding of reality. In Java, the fear was numinous – this is a goddess, this is holy dread. The interesting thing is how fear transitions to something else in the aftermath. After Nepal, Angell’s fear curdles into determination (he takes the book and runs, which is an act of both fear and courage). After Java, his fear melts into an almost beatific sense of peace (“he need fear no longer” because he has been accepted by the Goddess).

Levenda explicitly frames fear as transformative through his language.

“A part of him knew that he was falling apart… But another part of him knew that he was coming together… on the verge of a mental breakthrough.”

This is one of the clearest statements of the alchemy of fear. The stress and terror are breaking down the calcified structures of Angell’s mind, causing them to fall apart, so that a new, more enlightened structure can form and come together.

It’s almost textbook Jungian psychology – the confrontation with the Shadow, the psyche’s fragmentation, and then reintegration at a higher level. In mysticism, the concept is similarly well-known: the Dark Night of the Soul, characterised by despair, fear, and abandonment, precedes illumination or union with the divine.

Initiatory secret societies often include frightening tests in darkness, or the presence of memento mori (skulls, coffins) to invoke fear, precisely so that the initiate can transcend the fear of death and embrace spiritual rebirth. Angell’s fear on the beach is so intense he might break, but because he endures, it catalyses a breakthrough. He “survives long enough” to reap the reward of wisdom.

Beyond Angell, look at how fear operates for other characters and groups in the novels. The cultists of Dagon in Dunwich deliberately instil fear as a weapon – they engage in human trafficking and horrid rites, presumably to terrorise victims and perhaps use that terror in their rituals. There’s a suggestion that fear itself is a kind of energy they harness. This mirrors certain occult theories (for instance, the notion of loosh in some esoteric circles – that negative emotions can feed entities). On the flip side, the protagonists have to withstand fear to oppose such cults. There’s a scene in Dunwich where even hardened participants are frozen by the nightmares they’ve unleashed: “They were transfixed by sights that not even they… had ever experienced.” The fear cuts both ways; those who thought they controlled it become its victims. This is a cautionary element: if you wield fear irresponsibly, it will consume you.

Levenda doesn’t shy from depicting fear in its raw, visceral form. The climax of Dunwich reads like a horror fever-dream:

“Here were the Old Ones in complete flagrante delicto. All tentacles and tubings, gropings and viscous slimes, the bursting ichor of ancient beings celibate for aeons now let loose upon the brothel of the Earth.”

This grotesque, surreal tableau is meant to shock and horrify. It certainly invokes revulsion (and perhaps a guilty fascination) in the reader. Why go to such lengths? Because Levenda wants us to feel a fragment of what confronting an Old One would feel like – an overload of the senses, a violation of all norms (sexual, biological, logical), an encounter with the truly Other that evokes dread from the base of our reptilian brain. In that passage, he goes on to say that Lovecraft always kept sex off stage in his stories, only hinting at it, but that it was “the unspoken secret… the interface between human beings and the horrors… Sex was always there, off camera… It was the secret of Lovecraft, too.”.

By dragging this secret on stage in all its shocking glory, Levenda forces the confrontation. The reader cannot hide behind Victorian gentility as Lovecraft’s readers might; we are thrust into the orgiastic nightmare alongside the characters.

Why? Because that shock is instructive. It makes us viscerally understand the theme: that fear and desire are intertwined, that taboo-breaking is part of summoning the unknown, and that only by facing this can one comprehend the full Mythos.

It’s a high-risk strategy in storytelling – such passages are not for the squeamish – but it pays off in making the emotional truth hit home. We feel why these forces are terrifying and why one must be either insane or exceptionally brave (or blessed) to deal with them.

In the context of initiation, fear often plays the role of a threshold guardian. Levenda personifies this in different ways. One could say Cthulhu himself is the threshold guardian for Angell – the looming shadow that threatens to swallow him if he is unworthy. Or in a more benign form, the shaman Pak Mahmoud is a guardian figure who ensures Angell doesn’t succumb to fear. After the beach ritual, it’s the shaman’s steady gaze that draws in Angell’s wild-eyed shock and grounds him, confirming he has been saved. Thus, mentors and friends can help one process fear, just as in actual occult traditions, a guide or guru aids the initiate through the scary parts.

Levenda also illustrates how unprocessed fear leads to negative outcomes, whereas confronted fear leads to growth. Angell, at one point, was “full of hatred towards God” and in denial of any spiritual reality after his trauma in Mosul. That is a fear response turned outward as nihilism. It made him hollow and aimless (he admits to “self-loathing” before his transformative experiences). Living in fear (or in hatred, which is fear’s armour) shrank his world. Only by plunging into greater fears did he shake out of that state. It’s an interesting commentary: the fear of meaningless human cruelty was only answered when he faced the cosmic fear of something truly otherworldly. Paradoxically, the cosmic horror reintroduced meaning to his life – just not the old comforting meaning. Instead of renewing his faith in a conventional God, it opened him to gnosis of a hidden reality full of gods and monsters. In occult terms, one might say Angell moved from exoteric faith (which failed him) to esoteric understanding (which is hard-won, frightening, but ultimately more satisfying to him).

We can also consider how fear serves as a bonding agent between characters in the story. Shared danger forges alliances. Angell picks up allies along his journey (I suspect characters like the mathematician or other academics, perhaps even a covert agent or two, join his cause). Those who have seen “the elephant” (to borrow a term from Kipling – i.e., seen the terrible truth) recognise each other and stick together. This mirrors the real-life camaraderie in occult or paranormal research circles: once you’ve had a brush with the inexplicable, you find common ground with others who have, a fraternity of the initiated. Fear, once confronted, can turn into fellowship.

From a more metaphysical perspective, fear is also presented as a kind of initiation in itself. The title Tentacled Aeons of our previous article alludes to vast spans of time filled with monstrous beings – an image that inspires awe and fear at the immensity of creation.

We might recall Lovecraft’s line: “Fear is our deepest and strongest emotion, and the fear of the unknown is its most ancient expression.” Levenda’s work essentially agrees, but then asks: what if the unknown, once faced, could become known to some degree?

What if fear could be transmuted into insight? This is where Levenda’s perspective (as an occultist) diverges from Lovecraft’s (as a strict nihilist materialist). Lovecraft’s characters typically go mad or die when they confront the outer gods; knowledge is poisonous. In the Lovecraft Trilogy, knowledge is dangerous, yes, but it’s not inherently evil or fatal – it’s transformative. Those who misuse it or approach it with the wrong mindset suffer; those who approach with respect (and perhaps a bit of destiny on their side) can be changed for the better. Fear is the filter. It ensures only those who are ready get through. Angell’s name, interestingly, evokes “angel” – a messenger, one who brings knowledge from beyond. By the trilogy’s end, he has arguably become a kind of messenger himself, one who could convey this starry wisdom to others (if they’d believe him). To get there, he had to survive the gauntlet of fear.

Also, as we said already, “He need fear no longer,” the shaman says. In that simple statement is a profound notion: once you have confronted the ultimate fear (the “big one” – perhaps fear of death, or fear of the unknown), all lesser fears lose their power. Angell has been touched by something so immense that the ordinary anxieties of life – and even the threat of those government agents chasing him – likely pale in comparison. This is the fearlessness of the initiate who has seen the Mystery. It doesn’t mean he’s invincible or will never feel fear again, but it implies a kind of unshakeable core has formed in him. In occult schools, this is sometimes described as attaining the “Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel” (using a Western Hermetic term) or a state of enlightenment – one’s soul anchored in a truth that renders everyday horrors manageable.

For us, as readers and students of the occult, the takeaway is that fear can be a teacher. Levenda’s novels drive that home in Technicolor. The key is not to run from fear but to face it with eyes (and mind) open.

It’s a cautionary tale and an inspirational one at once. And it sets the stage for why someone might be drawn to study Mythos magick in the first place – not because it’s safe or comfortable, but because beyond the fear lies a rare and potent enlightenment.

Embracing the Black Stars: An Invitation

As we close this fourth excursion into the arcane, let’s reflect on how far we’ve come. Black stars hung in the sky of dim Carcosa when we started, beckoning us to follow their strange light. We answered in Dreamers in the Void, letting our minds wander through forbidden dreamlands in search of hidden gates. We wrestled with Tentacled Aeons, steeling ourselves to face the eldritch truths that slither at the edge of time. And now, guided by Peter Levenda’s esoteric storytelling, we have peered into a fictional grimoire and found reflections of our own occult journey. Through Angell’s trials, we vicariously tasted initiation; through Lara Kidul’s apparition, we sensed the dual faces of the divine; through unspeakable horrors, we learned how fear can be transmuted into insight.

The black stars of our course title were never just literal celestial objects – they are symbols of those obscure, powerful influences that shape destiny from behind the scenes. In Levenda’s work, one might say the black stars are the unseen hands of fate that led Angell to the Necronomicon and onto that beach where his soul was reforged. In our context, the black stars may be the faint pull you feel towards these arcane subjects – a pull that is both scary and exciting, ominous and full of promise. If you’ve felt that pull, if these discussions of Mythos magick and initiatory fiction ignite something in you, then you too are responding to the call of the black stars.

And so, a heartfelt invitation: join us in bringing this journey to its next stage. The Black Stars in Dim Carcosa course is gathering under those strange stars, ready to venture further into the unknown.

We’ll have Peter Levenda himself as our Virgil through the Inferno, shedding light on Lovecraftian mysteries and sharing his first-hand insights into the Simon Necronomicon. We will dive deeper into the very practices and concepts we’ve been exploring theoretically. Together, we’ll experiment with separating the masks from the faces – distinguishing fiction from reality, then perhaps realising that, in the realm of the occult, fiction becomes reality. Whether you’re a seasoned practitioner of the arcane or an intrigued newcomer who’s been following these essays with widening eyes, there is a place for you in this gathering.

In The King in Yellow, it is said that “strange is the night where black stars rise, and strange moons circle through the skies, but stranger still is...” – well, we all know what comes next in Cassilda’s song. Stranger still is the lost Carcosa. For us, Carcosa is not lost; it is being found, piece by piece, through the work we are doing. Levenda’s “fictional” Carcosa (by way of Lovecraftian lore) turned out to contain real maps and guideposts. Our own exploration will continue to blur those lines.

Already, figures like Michael Bertiaux step forward from the shadows of the text—his studio-temple overlooking Lake Michigan, his veiled references to Universe B, his cryptic sketches of Necronomicon physics—offering not just color, but keys. Bertiaux’s cameo reminds us that there are deeper strata still to uncover in Levenda’s work, and in the magical underworlds it mirrors. In a future installment, we may look closer at the Chicago magician and his occult cartographies—maps not just of place, but of potential.

So, if you have felt the tremor of dread and wonder in these words – if you have, perhaps, sensed your own part of self “falling apart and coming together” in following these tales – consider this a threshold. Cross it with us. Sign up for the course, step into the circle, and take your place among fellow seekers under the black stars.

The journey that awaits will be a reflective discussion come to life, an interplay of lecture and ritual, myth and practice. We will face fear (safely and constructively), we will seek contact (with our deeper selves, and who knows, perhaps with the benign “others” that watch from the wings), and we will undergo initiations large and small – together.

In the end, Starry Wisdom is not just the title of Levenda’s novel; it’s a state of knowing, a gnosis under the stars. It’s what we attain when we look up at the night sky – or into the pages of an uncanny book – and feel that mix of awe and terror, and choose not to look away. Starry wisdom is the wisdom of knowing our place in a vast, mysterious cosmos and daring to learn from intelligences greater (or stranger) than our own. It is, perhaps, the ultimate goal of Mythos-inspired magick: to take Lovecraft’s bleak cosmos and find within it the seeds of enlightenment, to transform cosmic indifference into cosmic initiation.

STARS & SNAKES IS OUT NOW

I’m pleased to announce something new: the release of Stars & Snakes: A Thelemite’s Field Notes—a collected anthology of these very writings, gathered together in one volume under my own independent Chnoubis Imprint.