DREAMERS IN THE VOID

Necronomicon Part II: “Simon”, Kenneth Grant, and the Mythic Engines of Postmodern Magick

Before we plunge into the depths of the Simon Necronomicon and the stellar gnosis of Kenneth Grant, take a moment to revisit the first article in this series. That initial piece laid the foundation for everything to come—introducing the central themes that will be explored in greater depth through written lessons, livestream sessions, and ritual practice as part of the upcoming course, Black Stars in Dim Carcosa. While this series is only the beginning, it is meant to prepare you—intellectually and magically—for the journey ahead.

BLACK STARS IN DIM CARCOSA

As I write these words on April 2nd, the shadow of cosmic memory lingers. Today is no ordinary date in the Lovecraftian calendar: it was on this day in 1925 that the events of The Call of Cthulhu were said to begin, when "every trace of Wilcox’s malady suddenly ceased."

Every occult bibliophile has heard whispers of the Necronomicon. Was it a mere invention of horror fiction, or a gateway to arcane truths?

In the late 20th century, two very different figures – an anonymous editor known as “Simon” and British magician Kenneth Grant – boldly blurred the lines between Lovecraftian fiction and esoteric reality. Their work, the Simon Necronomicon and Grant’s Typhonian writings, helped birth a subculture where fictional horrors became objects of gnosis.

In this article, I’ll narrow the focus and dive into the strange history of the Simon Necronomicon, its impact on occult practice in the 1970s and 80s, and Kenneth Grant’s eccentric interpretation of Lovecraft’s cosmic nightmares through a Thelemic lens. Along the way, we’ll explore the controversies: skeptics like Daniel Harms decrying the Simon book as a hoax and traditional Thelemites bristling at Grant’s departure from Aleister Crowley’s solar-phallic orthodoxy. By the end, we’ll see how both the Simon Necronomicon and Grant’s stellar vision left an indelible mark on postmodern occultism – a legacy at once fictional and profoundly real.

The Simon Necronomicon: A Modern “Ancient” Grimoire

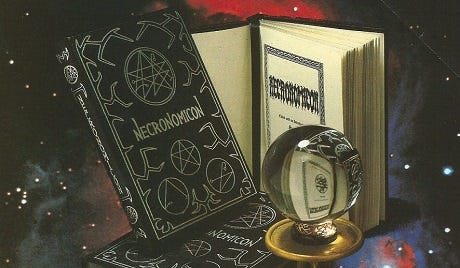

In 1977, a mysterious volume titled Necronomicon, attributed to one “Simon,” appeared on the shelves of occult bookstores. Billed as the ancient tome of forbidden lore that horror author H.P. Lovecraft had famously made up in his stories, this Simon Necronomicon presented itself with deadpan seriousness – as if the real Necronomicon had finally surfaced. Its contents were a curious blend: Sumerian and Babylonian mythological names and rituals mixed with nods to Lovecraftian entities and even a dash of Aleister Crowley’s magick.

The book is structured like a classic grimoire, complete with an 80-page editor’s introduction and a frame narrative called “The Testimony of the Mad Arab,” supposedly written by the Necronomicon’s unnamed author (an allusion to Lovecraft’s “Mad Arab” Abdul Alhazred). In these pages, readers find incantations, protective seals, conjurations of ancient powers, and cosmic warnings. The spells are a hodgepodge of languages – bits of English, Latin, Greek transliterations, and “barbarous” tongues – some taken from genuine Mesopotamian sources, others seemingly invented. The “Mad Arab” recounts discovering primal secrets and unleashing eldritch horrors, setting an ominous tone that lingers over the ritual texts.

From the start, the Simon Necronomicon courted controversy by design. The introduction (the only part “Simon” admits to authoring) spins a dramatic backstory: a Greek manuscript of the Necronomicon delivered by a defrocked monk, perilous experiments confirming its power, and dire warnings to any reader who would dare practice its rites. It even tries to connect the dots between Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, Crowley’s occult system, and “ancient Mesopotamian cults,” invoking parallels to Sumerian gods and Old Testament demons. Notably, the editors cite British occultist Kenneth Grant – who had speculated on a link between Crowley and Lovecraft – to lend an air of legitimacy. The book insists it predates Lovecraft, implying the author of The Call of Cthulhu merely tapped into this primordial source. It was a bold claim that many found as fantastical as Lovecraft’s fiction itself.

Yet for all its theatrical fakery, the Simon Necronomicon struck a chord. Marketed as “the most dangerous Black Book known to the Western World,” it promised real magical power – at a time when a new generation of occultists hungered for darker, more exotic pathways. First released as a limited hardcover by Schlangekraft, it reached mass audiences in a cheap Avon paperback in 1980. With its enigmatic sigils and spooky warnings, the book was an instant curiosity. I remember seasoned practitioners scoffing at it while younger occult newbies treated it like contraband to be read by candlelight.

By the 1980s and beyond, the Simon Necronomicon was continuously in print, eventually selling perhaps over a million copies worldwide. It became one of the most ubiquitous grimoires of the late 20th century, found not just in occult shops but mall bookstores and libraries – a pop culture phenomenon as much as an esoteric one.

From Hoax to Gnosis: Necronomicon Fever in the 1970s and 80s

The emergence of the Simon Necronomicon didn’t happen in a vacuum. The late 60s and 70s saw an occult revival that was increasingly flirtatious with the shadowy and bizarre. While the Necronomicon began as a fictional creation of H.P. Lovecraft (who always maintained it was make-believe), by the 1970s it had become the subject of serious speculation among occultists. In fact, the Simon book was one of several Necronomicon “hoaxes” that decade.

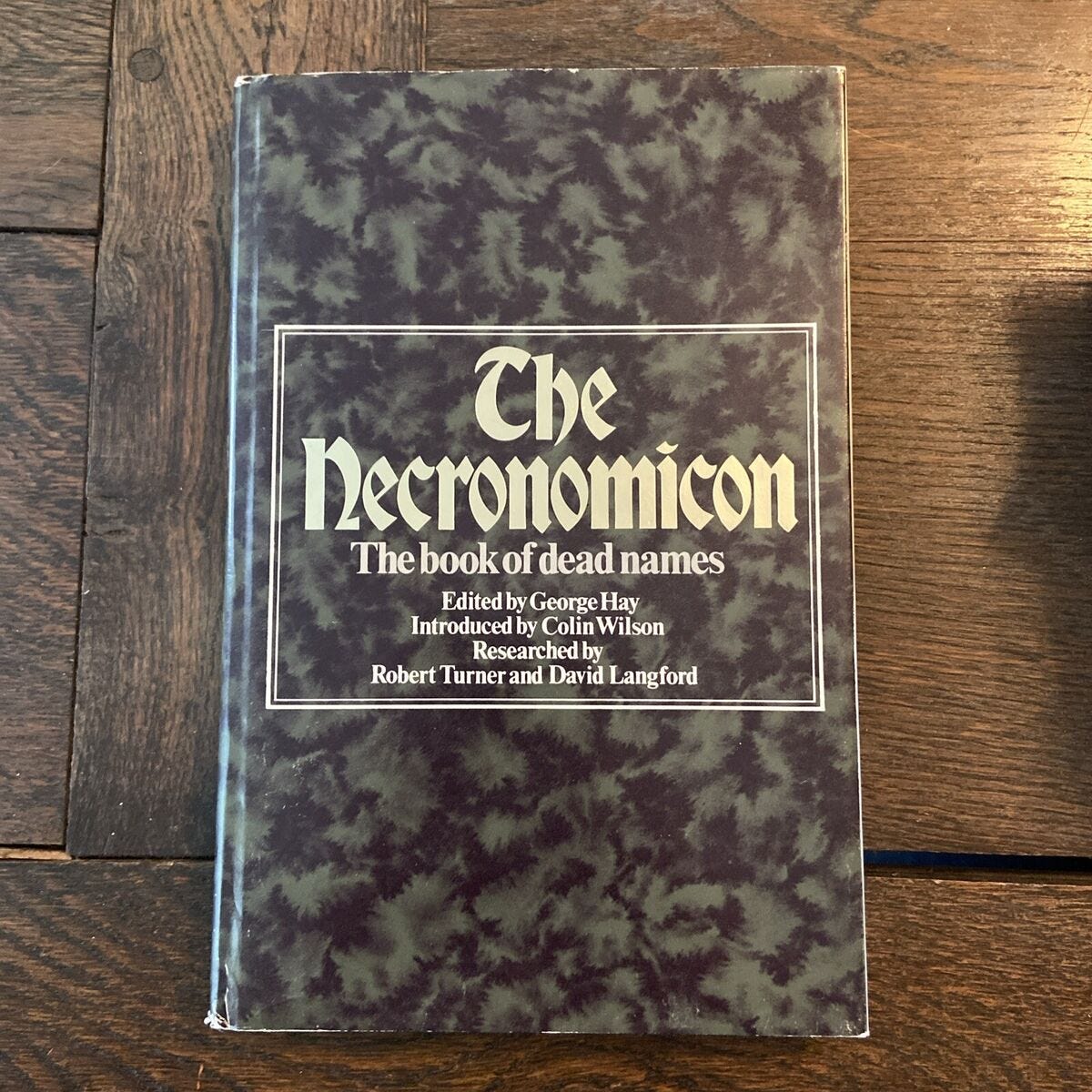

In 1978, British editor George Hay published a Necronomicon of his own, complete with a faux-history by writer Colin Wilson and pages of unreadable “Duriac” script as the text. Earlier in the ’70s, even science fiction author L. Sprague de Camp had joined in the prankish fun with a pamphlet called Al Azif (Lovecraft’s fictitious Arabic title for the Necronomicon), filled with gibberish characters pretending to be a translation.

Why this sudden will to will the Necronomicon into existence? Part of the answer lies in the shifting taste of the occult subculture. The hazy love-and-light mysticism of the 1960s was giving way to an appetite for the sinister and subversive. Anton LaVey’s Satanic Bible (1969) had popularised a rebel occult aesthetic, and in 1972 Michael Aquino (LaVey’s associate, later founder of the Temple of Set) actually composed Lovecraftian rituals like “The Ceremony of the Nine Angles,” openly borrowing from the Mythos. Occult bookstores like Herman Slater’s legendary Warlock Shop in NYC became hubs where one might overhear discussions of summoning Cthulhu alongside Goetic demons. When “Simon” walked into that very shop with a cardboard box allegedly containing the Necronomicon, the stage was set for a perfect mix of theatre and magick.

The Simon Necronomicon became foundational for a burgeoning “Necronomicon tradition” among practitioners. Despite (or because of) its dubious origins, people began working with it as a serious system of magic. By the 1980s, talk of “Necronomicon Gnosis” – a path of spiritual discovery using Lovecraftian symbolism and the Simon rituals – was gaining currency in certain occult circles. Some brave (or reckless) souls tried the book’s Gate-Walking rites, a series of initiatory trials through planetary gates described in the Simon text, seeking personal transformation or contact with the ancient Babylonian gods (Marduk, Ishtar, etc.) rebranded in Lovecraftian terms. Occult journals and neopagan zines of the era carried the occasional article on “Working with the Old Ones” or dream accounts of psychic contact with Cthulhu. Even famed Beat author William S. Burroughs, himself an experimenter with magic and cut-up technique, took interest – penning a 1978 essay on the paperback Necronomicon and musing on its reality (Burroughs saw reality as malleable fiction anyway).

Importantly, the Simon Necronomicon – and the craze it inspired – demonstrated a principle that would come to define postmodern occultism: the power of belief can make the fictional real. In the absence of a “genuine” ancient Necronomicon, occultists simply created one.

As one writer later noted, these 1970s grimoires, though hoaxes, have been used so often in rituals that they’ve spawned a real occult lineage, with folks “attempting to reconcile, reconstruct, and incorporate Lovecraftian occult material into a cohesive system” of magic. In other words, enough people believed in and worked with the Simon Necronomicon that – fake or not – it effectively became a magical reality. This embracement of fiction for spiritual ends was controversial at first, but it paved the way for the chaos magicians of the 1980s to declare that “nothing is true, everything is permitted” – if a made-up deity works for you, then it is real in your personal universe.

Kenneth Grant’s Typhonian Gnosis: H.P. Lovecraft, Thelemite?

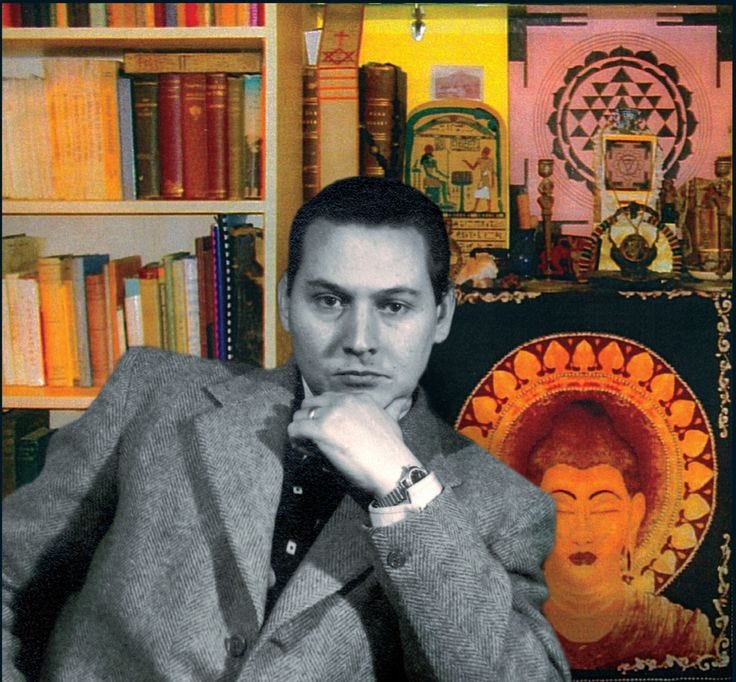

While “Simon” was busy cobbling together Sumerian mythology and Lovecraftian monsters into a DIY grimoire, across the ocean Kenneth Grant was doing something just as radical – but in a more high-minded, esoteric vein. Grant was a British occultist, a protegé of Aleister Crowley in the 1940s, who went on to found his own offshoot of Crowley’s order, the Typhonian O.T.O. Unlike most Crowley disciples, Grant had a wild visionary streak: he was convinced that H.P. Lovecraft’s tales of cosmic horror were more than just fiction – they were unconscious revelations of genuine occult truths. In his 1972 book The Magical Revival, Grant boldly suggested that Crowley and Lovecraft were unknowingly channeling the same occult forces – Crowley through his ritual magic, and Lovecraft through the dark dreams that inspired his fiction. This idea became a cornerstone of what he called the Typhonian Tradition.

Whereas Lovecraft fans might playfully ask, “Is the Necronomicon real?,” Grant’s answer was: on the astral plane, yes. He asserted that the Necronomicon exists as an “astral book” in the Akashic Records, accessible via dreams or magic, even if no physical copy exists.

To Grant, when Lovecraft wrote of the hideous grimoire and recited its alien incantations in stories, he was half-consciously tapping into an actual nightmare dimension – essentially serving as an unwitting scribe for forces outside time. Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones (Cthulhu, Yog-Sothoth, etc.), Grant believed, were real in the sense that gods and archetypes are real. They might not have physical form, but they existed as potent symbols or entities on the “night side” of the psychic cosmos.

Grant’s work throughout the 1970s and 80s meshed Lovecraftian mythology with Crowleyan Thelema, plus a heavy dose of Tantra, Qabalah, and surreal dream imagery. In books like The Magical Revival (1972), Aleister Crowley and the Hidden God (’73), Nightside of Eden (’77), and Outside the Circles of Time (’80), he spun an elaborate occult cosmology. For example, Grant identified Lovecraft’s fictitious deity Shub-Niggurath with the dark aspect of the Qabalistic Tree of Life, linking it to the Sumerian mother goddess and Crowley’s Scarlet Woman symbolism. He interpreted Lovecraft’s pantheon through Tantric concepts, seeing Cthulhu and company as akin to the fierce deities and energies awakened through Kundalini yoga and sexual magic (Grant was deeply influenced by Eastern mysticism). He spoke of opening “Gateways” to other dimensions – language very similar to the Simon Necronomicon’s gate-walking, though Grant’s gates were often the tunnels of the Qabalistic qliphoth (the shadow side of the Tree of Life). He even wove in UFOs and extraterrestrials as modern manifestations of the same ancient Lovecraftian dark truths – by the time of his later books, Grant was referencing alien lore and the occult significance of Sirius and Saturn in the same breath as Cthulhu.

To a newcomer, Grant’s writings can be bewildering. They are dense “transcripts” of dreams, visions, and arcane analyses – what one scholar called “verbal and conceptual labyrinths”. But the gist is this: Kenneth Grant treated Lovecraft’s fiction as a coded gnosis.

He believed Lovecraft had inadvertently mapped a portion of the occult reality that most occultists had overlooked – specifically, the “tunnels” of chaotic, primeval force beneath the orderly structure of traditional magic. Crowley’s system was solar and triumphant (the Age of Horus, the conquering child of the sun), whereas Lovecraft’s vision was cold, stellar, and filled with cosmic indifference. Grant found this “other side” compelling. As Peter Levenda (

) later wrote, Grant felt that Lovecraft uniquely “articulated the face of evil” – the utter alien darkness that most religious or magical systems prefer to gloss over. An authentic occult system, in Grant’s view, had to account for both light and darkness, wisdom and insanity, ecstasy and horror. By bringing Lovecraft’s grotesque pantheon into his magical worldview, Grant was essentially shining a blacklight on Thelema’s shadow side.In practice, Typhonian occultists under Grant’s influence started experimenting with Lovecraftian “dream magick.” They used Lovecraft’s stories as jumping-off points for astral journeys or scrying sessions, attempting to contact entities like Dagon or Shub-Niggurath in the astral temple. Some practiced sexual rites aimed at invoking Lovecraftian monsters (Grant’s texts include some eyebrow-raising accounts, such as the infamous “Rite of Ku” involving a form of auto-erotic ritual to summon a succubus-like entity – evidence of Grant’s fusion of Tantra with Mythos). It was heady, bizarre stuff – a far cry from the structured invocations of the Golden Dawn or the relatively simple candle-and-sigil spells of neopaganism.

Notably, Grant’s ideas even looped back and influenced the Simon Necronomicon’s introduction. The editors of the Simon book reference Grant’s notion of a connection between Crowley and Lovecraft, using it to bolster their claim that their grimoire is the true source behind Lovecraft’s tales. In this odd way, Grant’s scholarly occult musings provided a kind of “mythical validation” for the Simon hoax. It’s a lovely postmodern tangle: Lovecraft’s fiction inspires Grant’s occult theory, which inspires the Simon Necronomicon, which presents itself as the thing that inspired Lovecraft’s fiction! We’ve chased our tentacles in a full circle.

The Necronomicon Files: Purists vs. the Simon Legend

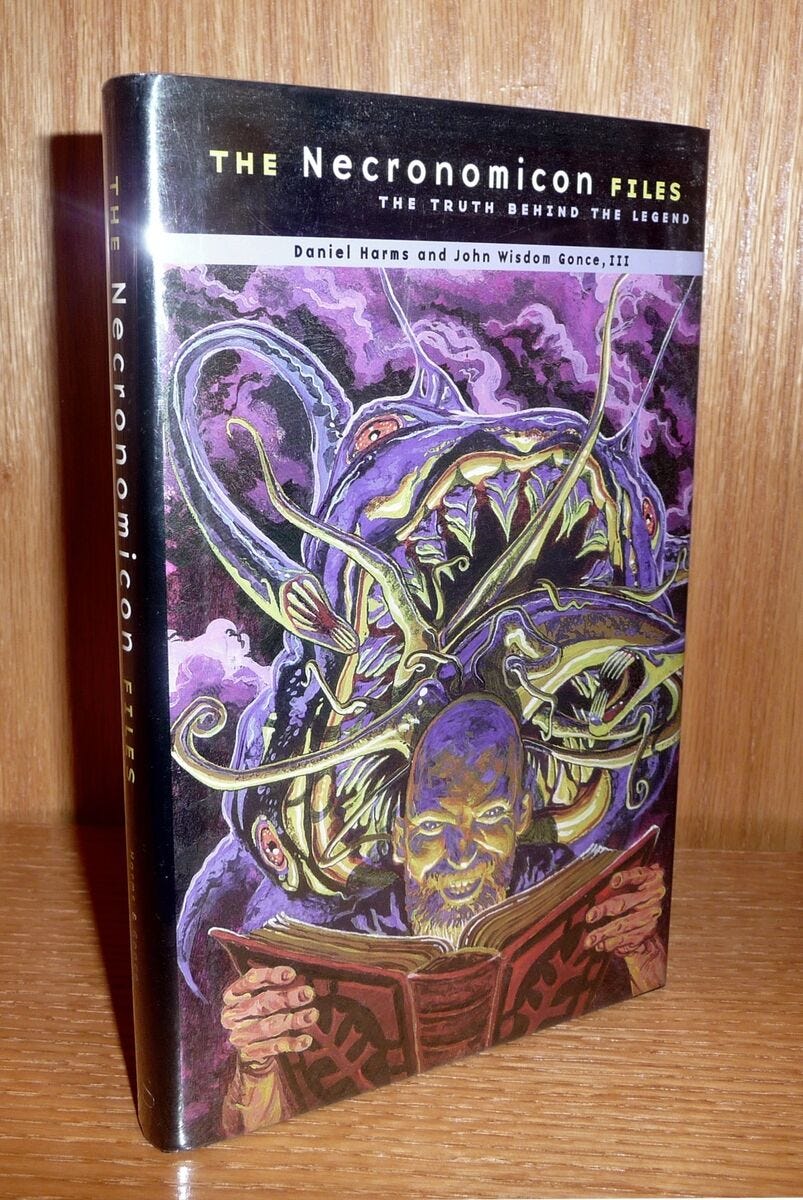

Whenever an occult text gains a following, sooner or later the skeptics and scholars arrive to crash the party. By the late 1990s, the Simon Necronomicon had plenty of true believers – and detractors. Two such investigators, Daniel Harms (a librarian and Lovecraft scholar) and John Wisdom Gonce III (an occult practitioner), teamed up to write The Necronomicon Files (first edition 1998, expanded 2003).

This book was a thorough debunking of Necronomicon lore and legend, and the Simon tome was squarely in their sights. Harms and Gonce meticulously traced the Simon Necronomicon’s content to its sources, demonstrating that large chunks were lifted from published mythological texts like R. C. Thompson’s Devils and Evil Spirits of Babylonia and other academic compilations of Mesopotamian spells. The “incantations” that weren’t outright quotes were often jumbles of Crowley material or gibberish. In short, the “ancient tome translated by a monk” story unraveled – separate translations don’t usually arrive word-for-word identical to public texts unless someone copied them!

Harms, approaching the subject as a grimoire scholar, took delight in exposing the Simon book as a patchwork fraud. He pointed out there was no evidence of any Greek original manuscript ever existing, nor any mention of a Necronomicon prior to Lovecraft. Every alleged historical link (from “Mad Arab” Abdul Alhazred to references in occult bibliographies) ultimately traced back to Lovecraft’s fiction or later pranks. By analysing everything from linguistic anachronisms in the Simon text to the testimonies of NYC occult community members, The Necronomicon Files made a strong case that Peter Levenda was likely “Simon” in disguise – something Levenda has denied, but many find plausible.

I certainly asked him many times, and eventually, I learned to live with the myth instead of chasing what might be the factual truth of the matter.

In any case, Harms and Gonce showed that all Necronomicons in print were, to put it bluntly, fake.

What made The Necronomicon Files especially interesting is that Harms and Gonce themselves embodied the split in opinion. Harms wrote from the dispassionate stance of a Lovecraftian researcher. His chapters read like a literature review and historical investigation: here’s what Lovecraft wrote, here’s who mentioned the Necronomicon when, here’s how the hoaxes were perpetrated, case closed. Gonce, on the other hand, as a practicing occultist, approached the topic with a bit more empathy (and, indeed, skepticism toward the skeptics). He wrote about the experiences of practitioners who used the Simon Necronomicon, including spooky anecdotes where people felt “something” answering when they performed the rituals. He catalogued the Necronomicon’s appearances in movies, music, and pop culture, treating it as a modern myth to be understood, not just debunked. This “Scully and Mulder” tag team made the book a nuanced read.

From Dan Harms’s scholarly perspective, the Simon Necronomicon deserved to be called out as fraudulent, especially if naive seekers were believing its tall tales. He and others sometimes express concern that newcomers might take the Simon book as a genuine ancient text and possibly put themselves at psychological risk by following its hazardous-sounding rituals (the text dramatically intones that improper use could be life-threatening, etc.). Harms highlights how Magickal Childe, the shop that published it, was well known for mixing prank and profit – selling a sensational story along with the spells.

Yet ironically, as Harms and Gonce point out, grimoires and hoaxes have always been intertwined. Many famous grimoires of history (the Key of Solomon, or the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses) are themselves pseudepigrapha – books written later and falsely attributed to ancient sources. As occult historian Owen Davies quipped, the Simon Necronomicon is “a well-constructed hoax,” but “it is their falsity that makes them genuine.” In other words, being a forgery doesn’t stop a grimoire from being used and becoming part of the authentic magical tradition. Scholar Dan Clore similarly noted that the hoax Necronomicons are “every bit as ‘authentic’ as” those old legendary grimoires – if by authentic we mean effective or influential.

This perspective might irk Harms’s academic sensibilities, but as Gonce likely would agree, by the 2000s the Necronomicon had transcended its fictional roots and become a modern myth. The Simon Necronomicon had inspired covens, magical orders, and countless solitary practitioners. Some claimed real psychic results from it; others blamed it for frightful encounters (perhaps psychological, but real to them). The genie (or djinn, or Great Old One) was out of the bottle – and no amount of scholarly debunking would erase the Necronomicon Gnosis that had taken hold.

Indeed, “Simon” himself (whoever he truly is) fought back against the critics. In 2006, he published Dead Names: The Dark History of the Necronomicon, a book-length rebuttal to Harms, Gonce, and other naysayers. In it, Simon doubles down on the conspiracy-laden backstory, tries to poke holes in the debunkers’ arguments, and insists there really was an ancient manuscript. Harms (on his blog) swiftly dissected Dead Names as well, calling it “Dead Names, Dead Dog” in a scathing review.

The feud only cemented the divide: on one side, occult traditionalists and Lovecraft scholars crying foul; on the other, a community of practitioners for whom, hoax or not, the Simon Necronomicon had become a valid spiritual tool.

Thelemites and Typhonians: The Solar-Phallic vs Stellar Debate

Kenneth Grant’s ventures into Lovecraftian magic were not universally applauded in the occult world either. In fact, Grant had already been something of an outcast within orthodox Thelemic circles since the 1950s. Some have argued that Karl Germer, Crowley’s successor as head of the O.T.O., was so disturbed by Grant’s inclusion of “extraterrestrial themes and Lovecraftian influences” in his New Isis Lodge rituals that he expelled Grant from the Order in 1955. The truth might be a little more prosaic, and that is that Grant always refused to charge fees and dues to member of his branch of O.T.O.

Traditional Crowleyan Thelemites – those who strove to preserve Aleister Crowley’s teachings as-is – viewed Grant’s innovations with suspicion or outright scorn. To them, Grant’s Typhonian Trilogy, full of alien gods and Cthulhu-esque monstrosities, looked like an almost heretical distortion of Thelema.

At the heart of this disagreement was what I’ll call the “Solar-Phallic vs. Stellar” worldview.

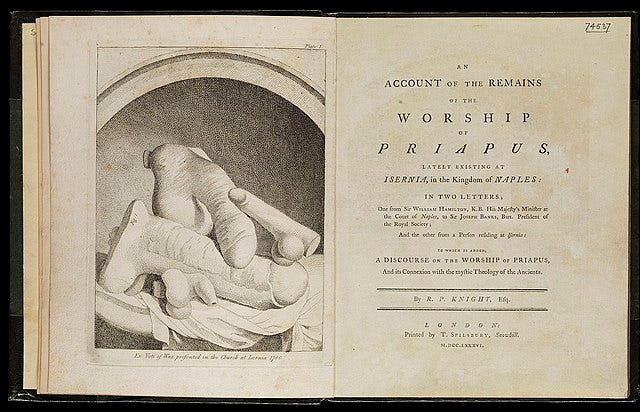

Crowley’s Thelema, as established in the early 1900s, was, in many ways, a product of its time. It drew on late-Victorian occult notions, including the work of thinkers like Hargrave Jennings and Sir Richard Payne Knight, who had theorised that all religion stemmed from ancient phallic worship of the Sun.

Crowley adopted this idea wholeheartedly: in Thelema, the Sun (symbolised by Ra-Hoor-Khuit, a solar-martial god, as the “visible object of worship”) and the Phallus (embodied in the male creative principle, often symbolised by the obelisk or lingam) are central symbols of spiritual power. Crowley’s Gnostic Mass is replete with sexual symbolism, elevating the phallus and womb to sacral status. This solar-phallic current celebrates the life-giving, light-bearing, generative forces of the cosmos. Thelemic magic in the early O.T.O. often revolved around these concepts – the magician (as Horus, the Crowned and Conquering Child of the Sun) asserting his Will much like the sun radiates light, often through the vehicle of sexual magic (the union of phallus and womb seen as a microcosmic reenactment of cosmic creation).

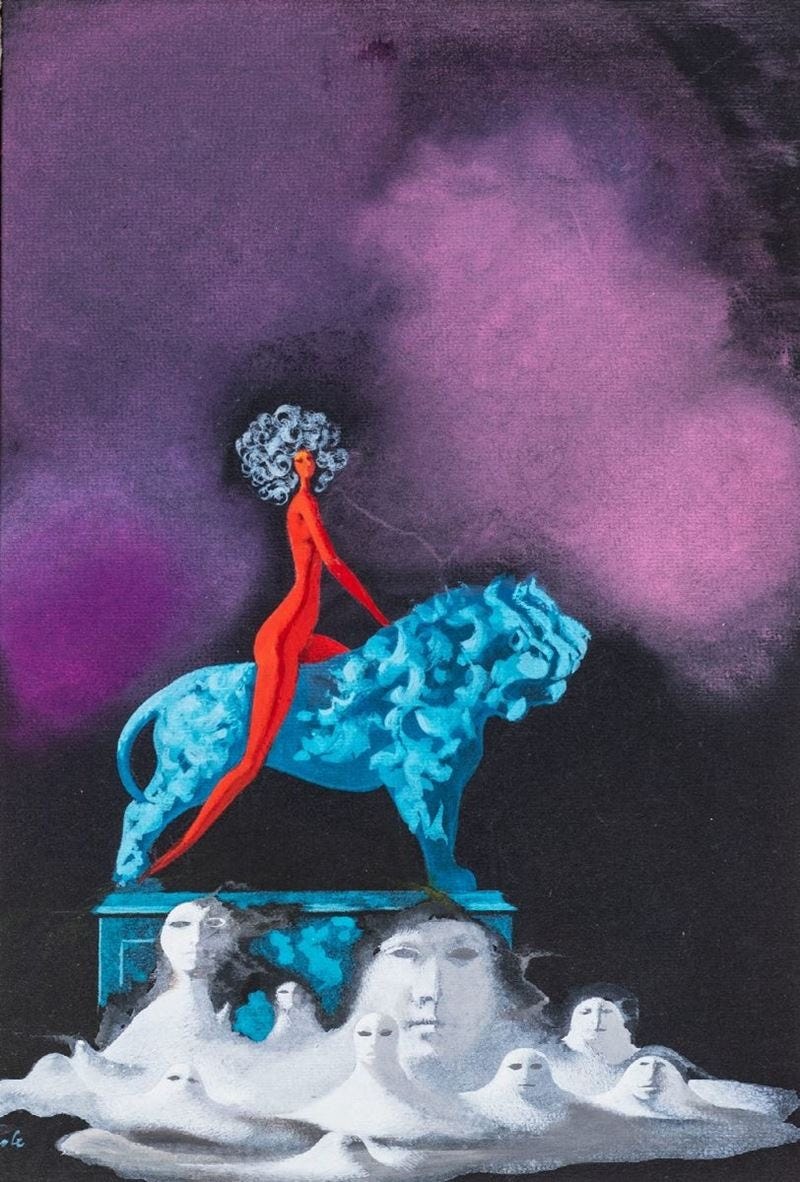

Enter Kenneth Grant, who said (in essence), that’s all well and good, but it’s only half the story. Grant shifted emphasis from the solar to the stellar; from the obvious male symbols of power to the mysterious, diffuse, and often feminine or non-human sources of power.

He looked to the stars – literally to star systems like Sirius and Orion, and figuratively to the “dark stars” of the unconscious. Instead of focusing on a rising sun of a new Aeon, Grant was fascinated by the void between the stars, the vast gulfs of deep space where Lovecraft’s Ancient Ones lurked. His was a “Typhonian” current – Typhon/Typhoeus being a monstrous primordial in mythology, and also associated by Crowley with the backward Qabalistic sphere of Da’ath and the star Set (identified with Sirius). Grant’s Typhonian Order placed a big emphasis on the goddess aspect too – invoking Nuit, the starry sky goddess in Crowley’s cosmology, and Ma’at, the Egyptian goddess of truth whom Grant speculated would herald a future Aeon beyond Horus. In fact, one of Grant’s contemporaries (and students), the priestess Nema, received a mystical text (Liber Pennae Praenumbra) in 1974 that announced an incoming “Aeon of Ma’at,” complementing Crowley’s Aeon of Horus. Grant enthusiastically supported these ideas, whereas orthodox Thelemites balked –while The Book of the Law does allude to the coming of future Aeons beyond that of Horus, it never directly mentions Ma’at by name, leaving some to question the origins of these newer revelations.

To traditional Thelemites, Grant’s embrace of Lovecraftian “alien” gnosis and talk of extraterrestrial occult intelligences all seemed like a dangerous deviation. Crowley had certainly pushed the envelope in his time, but Grant was venturing into territory that hadn’t even been considered part of “serious” occultism. Some likely thought he was delusional or mixing fiction with fact irresponsibly. It didn’t help that Grant’s writing style could be extremely abstruse; many Thelemites simply couldn’t understand what the heck he was proposing half the time, only that it didn’t sound like the straightforward “Do what thou wilt” and holy phallus doctrine they were used to.

From Grant’s perspective, however, Thelema needed to evolve. He saw himself as expanding Crowley’s system to have a “more global character”, incorporating threads from Hindu Tantra, Afro-Caribbean voodoo, and even Yezidi and Sumerian lore, weaving them all into Thelema’s framework. In essence, Grant’s work tried to give Thelema a broader, inclusive scope – one that could address the entirety of the human magical experience, from the heights of mystical union to the darkest corners of the subconscious. He wasn’t abandoning Thelema’s solar-phallic core; rather, he was supplementing it with a “stellar gnosis” – a recognition of the starry infinite (Nuit) and the possibility of contacting trans-human or supra-human intelligences (whether you call them gods, extraterrestrials, or archetypes from the collective unconscious).

It’s quite forward-thinking if you consider where the occult world was headed. In the decades after, the idea of working with non-traditional mythologies (from Lovecraft’s Mythos to comic book characters in chaos magick) became almost commonplace.

Grant was a pioneer in that sense, dragging Thelema away from the Edwardian parlor and into the weird, psychedelic space-age era. But he did so in such an esoteric, poetic fashion that many of Crowley’s more down-to-earth disciples just shook their heads. To them, Grant’s “stellar” focus seemed ungrounded, even dangerous – was he suggesting we summon actual Lovecraftian demons? (Grant, to be fair, did include plenty of cautions and symbolic interpretations, but sensational rumors spread anyway.) They also questioned his sources – Crowley at least pretended to get his teachings from ancient Egyptian gods and real secret chiefs; Grant was openly citing pulp horror fiction as inspiration! The orthodox folks likely saw that as a blurring of fantasy and reality that could discredit Thelema.

Another point of contention was Grant’s willingness to deviate from Crowley’s literal word. For traditional Thelemites, The Book of the Law and Crowley’s corpus were (and remain to this day) quasi-scriptural. Grant treated them more like launch pads for further gnosis. In his books, he even suggests that Crowley himself might not have fully understood some of the cosmic currents he was dealing with – a somewhat blasphemous notion in O.T.O. circles. As an example, Grant speculated that Crowley’s 1918 “Amalantrah Working” (a series of visionary experiences Crowley had in New York, wherein he allegedly contacted an entity called Lam) might have opened a portal that allowed Lovecraftian forces to begin infiltrating human consciousness – an idea both fantastical and charmingly synchronistic (Crowley does a ritual in 1918; Lovecraft writes The Call of Cthulhu in 1926, voila!). Traditionalists likely rolled their eyes at such claims.

The debate between Typhonian vs. traditional Thelema essentially boils down to how flexible one thinks a spiritual tradition can be.

Crowley’s system was itself revolutionary in its time, synthesising Eastern and Western, ancient and modern. Grant took that syncretism to the next level, adding science fiction, surrealism, and shadow work. In doing so, he arguably helped “transform the hegemonic masculinity” of Western occultism, opening the door for more fluid, diverse expressions of magick (chaos magick and the rise of divine feminine currents, for example). But he also alienated those who preferred the familiarity of the old symbols like the Sun, the Lion, the Phallus standing triumphant – imagery which, as we noted, came from Victorian interpretations that have since been academically debunked or at least tempered. Modern scholarship doesn’t think all religion reduces to phallic sun-worship; yet Crowley’s system was built with that assumption. When Grant exchanged the “solar-phallic” lens for a “stellar-sinister” one, he was in a sense updating Thelema’s underpinnings – but not everyone wanted those underpinnings updated.

In the end, the critiques of Grant within Thelemic circles never really derailed him – he continued writing and leading his Typhonian Order until his death in 2011. Today, the Typhonian tradition is recognised as a legitimate branch of Thelema, even if the main O.T.O. doesn’t endorse it. Interestingly, some Thelemites have come around to appreciating Grant’s contributions, especially as the rest of occult culture caught up to his ideas. At the time, though, his melding of Lovecraft and Crowley was truly controversial – much as the Simon Necronomicon was controversial among purists of ceremonial magic.

Legacy: Fiction, Gnosis, and the Postmodern Occult

Half a century ago, the notion of invoking “gods” from horror fiction or crafting a hoax grimoire and watching it become real would have sounded absurd. Today, in our postmodern occult milieu, these things are almost taken for granted. The influence of both the Simon Necronomicon and Kenneth Grant’s Lovecraftian gnosis is woven deeply into the current esoteric landscape.

Their legacy is evident in multiple facets:

Lovecraftian Occultism as a Genre: Thanks largely to Grant, occult bookstores now have an entire subsection for “Cthulhu Mythos Magick” or “Lovecraftian sorcery.” Dozens of books and grimoires have been published that expand on this theme – from Necronomicon spellbooks to ritual guides like Asenath Mason’s Necronomicon Gnosis (2007) which explicitly builds on the Simon material, Grant’s work, and chaos magic techniques. There are magical orders (e.g. the Esoteric Order of Dagon, founded in the late 1980s) that explicitly work with Lovecraftian imagery. What was once fringe (or a joke) is now an established path for some occultists. Justin Woodman, an anthropologist, noted that Grant was “one of the key figures” responsible for bringing Lovecraft’s fictional universe into magical practice, having a “formative influence” on these Lovecraftian occult groups.

Chaos Magick and Pop Culture Magick: The radical idea that belief is a tool and that even fictional entities can be invoked as gods found a natural home in the Chaos Magick movement of the 1980s and 90s. Peter J. Carroll and Phil Hine, some of the earlier movers and shakers of Chaos Magick, were directly or indirectly influenced by both Grant and the Necronomicon phenomenon. Hine wrote The Pseudonomicon (1994), treating the Lovecraft Mythos as a playground for personal gnosis – essentially taking Grant’s and Simon’s ideas but shedding the pretensions of authenticity. Chaos magicians happily summon Cthulhu one day and Thoth the next, knowing both are thought-forms they can harness. The early adoption of Lovecraft by the occult community paved the way for this postmodern flexibility. As the deepcuts blog neatly summarised, Simon presented the Necronomicon as “real,” Grant asserted Lovecraft stumbled onto occult truth, and chaos magicians simply acknowledged Lovecraft made it all up – but chose to work with it anyway. The latter stance has become increasingly common. In the 21st century, you’ll find occultists invoking everything from Sherlock Holmes to Sailor Moon in their spells – and that spirit of “fiction-as-magick” really gained momentum with the Necronomicon craze and Grant’s work.

The Simon Necronomicon’s Ongoing Mystique: Despite all the debunking, the Simon Necronomicon continues to be practiced and adored (in some corners) and reviled (in others). It has the unique status of being both a pop culture artifact (name-dropped in movies, music, games – e.g. the Evil Dead franchise’s creepy Necronomicon Ex-Mortis prop owes a debt to the Simon visuals) and a serious spiritual tome for those who have found meaning in its pages. Some occultists swear by its Sumerian gate-walking system for self-initiation. A few even formed small groups dedicated to the “Necronomicon tradition,” sharing gnosis and personal UPG (unverified personal gnosis) on forums and blogs. The book’s cultural legacy is such that even people who’ve never read Lovecraft recognise the word “Necronomicon” – it’s entered the zeitgeist as THE occult book of shadows. And somewhere out there, I guarantee, right now someone is nervously chanting one of “Simon’s” incantations, hoping to glimpse an Ancient One or open a forbidden gate. I know I will be doing exactly that in a few week’s time, and you are welcome to join me and many others.

Thelemic Evolution and the Typhonian Influence: Kenneth Grant’s ideas, once on the fringe, have permeated modern occult thought. The mainstream O.T.O. may not endorse talking to Cthulhu in one’s spare time, but the wider Thelemic community has grown to accept that Crowley’s system can be approached in multiple ways. Grant’s emphasis on Nuit (the stars) and the Nightside helped inspire later occultists to explore the divine feminine and the shadow. Today, practices like shadow work, Qliphothic Qabalah, and syncretic approaches that blend Western magic with Eastern Tantra (and yes, occasional Lovecraftian spice) are relatively common. You see it in the rise of groups like Dragon Rouge (a magical order from Sweden focusing on Qliphoth and dark gods) and in the work of magicians like Michael Bertiaux and Andrew Chumbley – all of whom were influenced by or at least aware of Grant’s trailblazing. The idea of a future Aeon of Ma’at has also gained traction in some Thelemic offshoots, validating Grant’s forward-looking instincts.

Ultimately, the legacy of the Simon Necronomicon and Kenneth Grant’s Lovecraftian Thelema is a testament to the creative power of the human psyche. They taught us that myth can be made real through belief and practice. This has a flip side: it also means discerning truth becomes trickier. We have to navigate carefully – separating deliberate fiction from personal revelation, and hoax from genuine experience – often with only our intuition and results as a guide. But perhaps that is the point in this postmodern magical age.

Toward the end of Necronomicon Gnosis, Asenath Mason writes something that encapsulates this new paradigm. She acknowledges that all published Necronomicons are considered hoaxes, “none of them is the ‘genuine’ Necronomicon.” Yet, she urges readers not to be discouraged: “Magical power is not contained within any written book but within our minds, and a mind of a creative individual can transform fiction into a genuine experience. In this sense we can use the Lovecraftian lore as a tool in exploration of dark labyrinths of our mind.”. This is a powerful statement of the ethos that both Simon and Grant (each in their own way) embraced.

The Simon Necronomicon began as a literary prank and became a portal – for some to genuine mystical insight, for others to self-delusion, but undeniably to something beyond the ordinary. Kenneth Grant took a detour through the twisted mountains of Lovecraft’s imagination and found hidden valleys of initiatory wisdom there. Between fiction and gnosis lies a fruitful, if misty, realm – one rife with controversy, yes, but also with creative potential.

As a lifelong student of the occult arts, I find something poetic in that. The Necronomicon was never “real” in the historical sense, yet it inspired real magic. Lovecraft never believed in his own monsters, yet they found their way into rituals that genuinely transformed people’s lives. Perhaps the greatest lesson here is that belief is a magical act in itself. We choose what to believe into existence. In doing so, we must also take responsibility for our creations – whether that’s a contrived spellbook that takes on a life of its own, or a magical theory that challenges the status quo.

The story of the Simon Necronomicon and Kenneth Grant shows that the walls between imagination and reality are thinner than we think. In the end, “That is not dead which can eternal lie,” as the Mad Arab wrote in Lovecraft’s lore – and with strange aeons, even a fictional idea may arise into truth.

Ready to take the next step? Enrollment is now open for Black Stars in Dim Carcosa—but space is limited. This is your chance to explore the Necronomicon current through structured lessons, guided rituals, live Q&A sessions, and discussions with our very special guest, the Peter Levenda.

Please note: all course materials will only remain accessible until October 12th, marking the 50th anniversary of the Simon Necronomicon’s first publication. After that, the gates will close.

STARS & SNAKES IS OUT NOW

I’m pleased to announce something new: the release of Stars & Snakes: A Thelemite’s Field Notes—a collected anthology of these very writings, gathered together in one volume under my own independent Chnoubis Imprint.

Interesting choice of colours there especially the creature gives my heart a wee pang.

Again a most interesting read. And while I know Crowley and a number of his books in original and translation, I would not dare to claim to share all his views or understand them all. But I do enjoy his mastery of language.

Grant was and is new to me. But your well-written article has made his thinking and his work very clear. And by the way, the Typhonian OTO appears to be an appropiately chosen name with Typhoeus/Typhon being described by Nonnos (Dionisiaca book 1, loc.var.) as an entity with many arms and a mouth like an abyss (1,220 - 225 et al.) - an early image of Cthulhu.. Grant must have known that I think. And my Simon Necronomicon has disappeared from my bookshelves...is that a hint?

Thank you very much again for this thought-provoking piece. All the best. I will have to check some things out.