“…we are telling the truth in spite of ourselves—serving unwittingly as mouthpieces of Tsathoggua, Crom, Cthulhu, and other pleasant Outside gentry.” — H. P. Lovecraft

The Fiction That Dreamed Itself Awake

In a half-jesting 1933 letter, H.P. Lovecraft suggested that he and his fellow weird tale writers might be unwitting heralds of things beyond human conception. The man who insisted his horrors were fictional thus hinted (perhaps unknowingly) at a strange truth: that mythic forces can speak through invented stories.

Decades later, this ironic premonition has borne fruit. The boundary between fiction and occult reality has grown porous; what began as imaginative dread in pulp pages has seeped into the practices of living magicians. We stand today in an uncanny age—tentacled aeons, one might call it—where Lovecraft’s dark mythology has not only spawned new myths, but actual rites and paths of initiation. Myth has bled into praxis, giving rise to diverging currents within contemporary Lovecraftian occultism, each winding toward the nameless Outer Gods in its own fashion.

During Lovecraft’s lifetime, readers sometimes asked whether his forbidden grimoires and eldritch entities were real. Ever the rationalist, Lovecraft assured them it was all make-believe. Yet the very act of imagining those “outside gentry” planted seeds. In time, occultists did begin to appropriate elements of the Cthulhu Mythos.

As we saw in the previous articles in this series, by the 1970s, notable figures like Kenneth Grant—Aleister Crowley’s maverick disciple—were openly grafting Lovecraftian and cosmic themes onto esoteric practice. Even Anton LaVey’s Satanic Bible paid homage to Lovecraft’s names. The 1970s also saw the rise of the Necronomicon hoaxes: books by authors like “Simon” and George Hay that presented themselves as the very Necronomicon Lovecraft invented. Complete with sigils and incantations, these texts purported to be genuine grimoires. Of course, they were modern fabrications—but in masquerading as “real” they inadvertently gave occultists a tangible focal point for Lovecraft’s lore.

Thus, a peculiar Necronomicon Current in occult literature was born: a growing body of work trying to reconcile and expand Lovecraft’s Mythos into a cohesive magical system. In short, Lovecraftian fiction birthed a living mythology, and that mythology, in turn, birthed a praxis. What were once fictional names began to be intoned in candle-lit circles; what was once just story became scripture of a sort.

Two Paths Through the Mythos

As this Lovecraftian occult movement evolved, two distinct yet resonant strains of magical engagement emerged. They share a reverence for the “outside” and a willingness to blur reality’s edges, but they diverge in philosophy.

On the one hand, there are those who treat Lovecraft’s creations as actual cosmic forces—real in some supra-physical sense, awaiting contact. This camp, inspired by pioneers like Kenneth Grant, believes Lovecraft’s tales concealed objective esoteric truths. In their view, the dreaded Necronomicon may well exist as an astral book, and the Great Old Ones and Outer Gods are more than fiction: they are genuine entities or symbols of ancient powers that can be approached through ritual.

On the other hand, we find those who approach the mythos as a powerful modern mythopoeia—a deliberate fantasy that can be used as a toolkit for self-transformation. These practitioners, often influenced by chaos magick, fully acknowledge that the Lovecraftian gods began as fiction, yet proceed to treat them as if real for the purposes of sorcery and inner exploration. To them, whether Cthulhu “exists” is almost irrelevant; what matters is that the idea of Cthulhu, fueled by human imagination and belief, can galvanise the psyche and open doors to the Unknown. In short, one current looks outward to an alien reality they believe is truly there; the other looks inward, using “alien” symbols to discover uncharted regions of the self. Both currents wind through the haunted landscapes of Lovecraft’s imagination, but their destinations differ—one towards cosmic communion, the other toward personal gnosis.

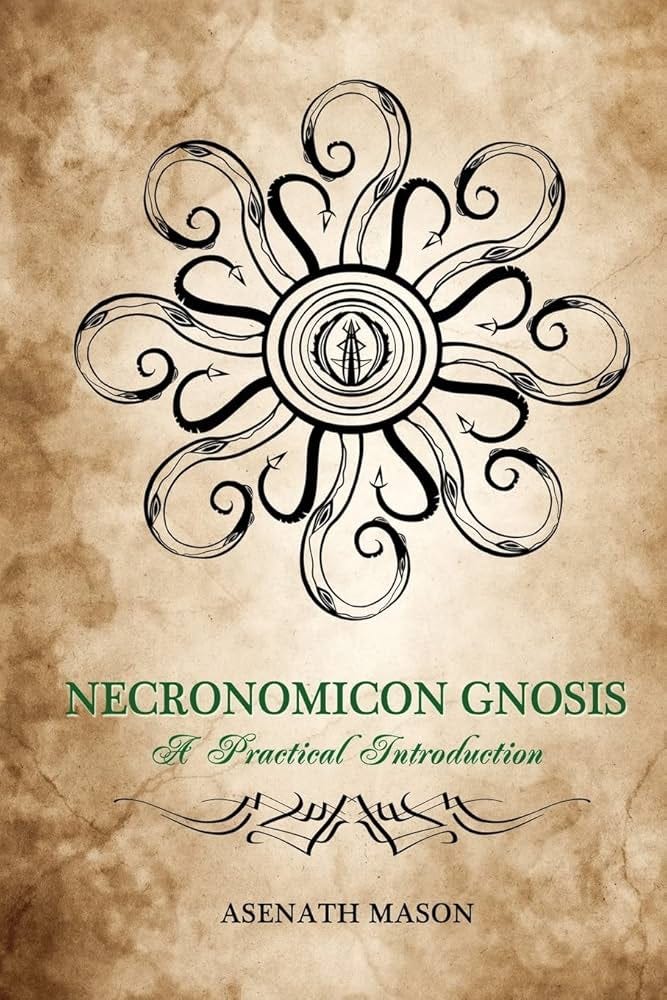

Asenath Mason exemplifies the second approach: treating the Lovecraftian Mythos as a living egregore and paradigm for inner initiation.

In her work Necronomicon Gnosis, Mason confronts the fact that every published Necronomicon is a hoax or pastiche. Rather than bemoan this, she embraces it. “None of them is the ‘genuine’ Necronomicon… This fact, however, should not discourage us from working with these texts,” she writes, noting that “magical power is not contained within any written book but within our minds, and a mind of a creative individual can transform fiction into a genuine experience”. In other words, the idea of the Necronomicon – the very egregore of it – is what matters. The imagination and will of the practitioner are what give it reality. Lovecraftian lore can be used as a tool to explore the dark labyrinths of our mind, Mason argues, echoing the core ethos of chaos magick: that belief is a tool and myth can be programmed into the psyche to produce real effects. Indeed, her philosophy aligns with occult thinkers like Phil Hine, who treated fictional constructs as valid grist for magick (at least in his early chaos magick days). To a 21st-century magician, as Mason notes, a name like Cthulhu can be as potent as an age-old god like Osiris – both are meaningful symbols to conjure with.

Following this ethos, Mason’s magical practice focuses on gnosis – the direct spiritual insight gained through experience – rather than on external phenomena. Her rituals do not promise the showy miracles of pulp fiction; you won’t find her trying to literally summon a tentacled titan to rise from the sea or resurrect corpses from their graves.

Indeed, during the nighttime conjuration of Dagon, in that long-gone summer of 2003 by shores in Ostia, nothing physical came to greet us... but something did emerge from the depths of our collective inner sea.

Instead, the workings in Necronomicon Gnosis aim at the initiate’s transformation. They are often meditative, visionary, and psychologically intense, seeking to expand consciousness and catalyse self-initiation. The horror tropes of the mythos become metaphors and gateways for inner change. For example, one of Mason’s rites, “The Black Communion,” is an invocation of Shub-Niggurath, the primordial fertility deity in Lovecraft’s pantheon. In Lovecraft’s stories Shub-Niggurath is a monster – “The Black Goat of the Woods with a Thousand Young” – but in Mason’s ritual this entity is approached as a wellspring of chthonic and feminine power. The ceremony directs a priestess to envision the goddess and fully identify with her, arousing the Kundalini “serpent” energy and inflaming primal, insatiable lust so that “the consciousness of the entity and the priestess become one”. In effect, the practitioner uses the alien image of Shub-Niggurath to invoke a deeply human archetype: the untamed goddess of fertility and desire, freeing and empowering herself through that identification. What was a terror in fiction is transmuted into a sacrament in practice. Mason’s path is thus deeply introspective and alchemical. Each Outer God or tome or symbol becomes a mirror—revealing aspects of the self through the funhouse reflection of eldritch myth. The aim is awakening: expanding the mind’s boundaries by journeying through dream, symbol, and shadow. It is a solitary and mystical road, walked in the inner landscape as much as (or more than) in the external world.

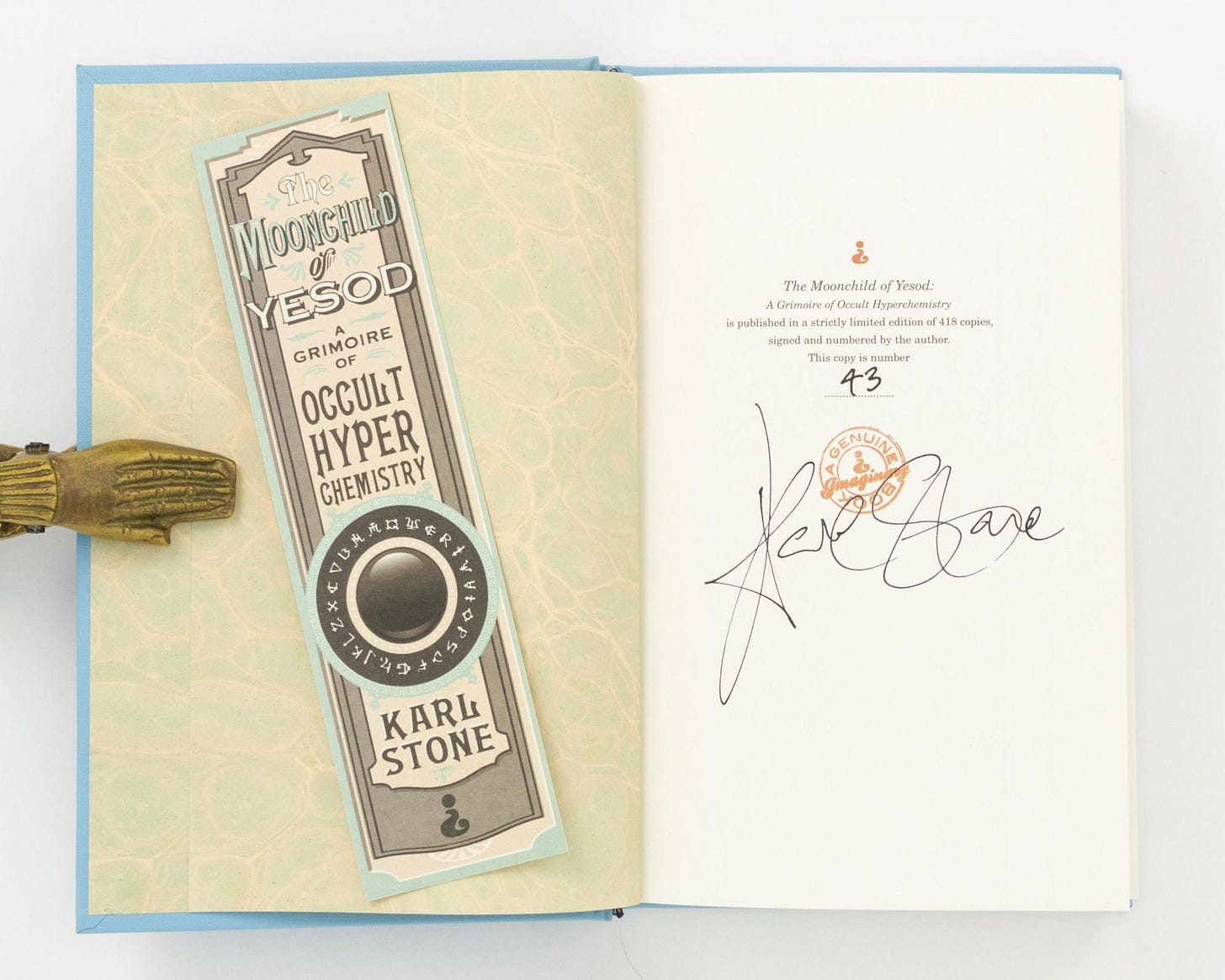

Karl Stone, by contrast, stands as a champion of the first approach: he treats Lovecraft’s mythos as an esoteric reality to be directly explored.

If Mason is the subtle mystic of the Mythos, Stone is the visionary theurgist. Styling himself “a Hyadean emissary of the Cult of the Yellow Sign” – a title pulled straight from the nebulous lore of Carcosa and the King in Yellow – Stone blurs the line between role-play and revelation. With a flair for the dramatic, he has built a labyrinthine magical system that actively incorporates Lovecraftian forces alongside classic occult lore. In his magnum opus, The Moonchild of Yesod: A Grimoire of Occult Hyperchemistry, Stone “builds on the work of Mme. Blavatsky, Aleister Crowley, and Kenneth Grant to construct a Magickal Mirror that opens a genuine Gateway to Beyond”. In other words, he views the Lovecraftian pantheon not as a psychological metaphor but as part of the literal spiritual landscape one can traverse. For Stone, the Outer Gods and Great Old Ones are pieces on the chessboard of the cosmos, just as the gods of Egypt or the angels of kabbalah are—each with their sigils, rites, and secret names. His writings gleefully intermingle Theosophical mysticism, Eastern tantra, Thelemic sex magick, and Lovecraftian nightmare imagery into one heady brew. The chapter titles of Moonchild of Yesod range from analyses of Tarot dynamics and Kabbalistic “50 Gates of Understanding” to instructions for “hallucinatory vortices” and “tentacled…gateways to other worlds”. Indeed, the work promises “obscure rites and practices” that produce “the dislocation of the mind, and the deep penetrative insight that arises from these territories”. This is the vocabulary of someone attempting to literally venture into the Beyond — to push consciousness so far that it might brush against the truly alien.

If Mason’s emphasis is on the mind’s creative power, Stone’s emphasis is on breaking the mind open to receive something truly Other.

Stone’s style is as extravagant as his methods. By his own account, he is a Discordian episkopos and an “occult mycologist,” a practitioner of sacred fungi and surreal wisdom. There is a tricksterish humour in his self-presentation (the very idea of a “Bone Setter” hyperchemist from the Trans-Himalayan tradition” wearing the Yellow Sign suggests a wink), yet beneath the colourful masks lies sincere intent. Stone takes seriously the idea that Lovecraft’s fiction can be leveraged to pry open the doors of perception. If some laugh at the notion of chanting incantations to Cthulhu, Stone would likely respond that such laughter itself is part of the Discordian initiation – a way to dispel fear and dogma before the real work begins. Once the wit and absurdity have cleared the air, the ritual proper commences. In that ritual, Stone might call upon Yog-Sothoth as a lord of hidden gates, or Azathoth as a force of primordial chaos to dissolve ordinary reality. He infuses these workings with the full arsenal of traditional occultism: astrological timings, sex-magical techniques, and hermetic correspondences. The result is an experience designed to be as real as possible for the participants. In Stone’s universe, to invoke Nyarlathotep is not done simply to play-act a scene from a story; it is to genuinely invite the Crawling Chaos into one’s temple and one’s soul. Such a path is not for the faint of heart or the ungrounded. It is an ecstatic, potentially disorienting dance on the edge of reason. But for those who crave a direct encounter with the Unknown, it offers a wild and heady promise: contact. Contact with forces outside the circles of ordinary human experience, and through that contact, the attainment of wisdom or power impossible to derive from more conventional spirituality.

The Dream Is the Initiation

On the surface, Mason’s and Stone’s currents could not be more different. One is contemplative, psychological, and cautious; the other baroque, ceremonial, and bold. One turns the gaze inward, the other outward. Yet they are two poles of the same magnet, two complementary faces of the Lovecraftian occult impulse.

Both understand that myth is a living thing. Both take Lovecraft’s mythos seriously—not as literal-minded dogma, but as a font of practical symbols and ritual inspiration. In Mason’s quiet dream-work and Stone’s elaborate summonings alike, we see the same core principle: that engaging with the frighteningly alien can trigger profound transformation. The mythos provides a context in which terror and wonder can be experienced safely (within the container of ritual or inner journey) and thereby harnessed. In both streams, the practitioner is effectively stepping into a story—walking through the pages and into the dream. The dream-logic of modern initiation is fully at play here. Initiation in these Lovecraftian currents is rarely a straightforward, linearly scripted affair. It often comes through uncanny synchronicities and surreal experiences that mirror the illogical narratives of nightmares. As Kenneth Grant observed, Crowley’s reception of The Book of the Law, Austin Osman Spare’s trance-art magic, and Lovecraft’s cosmic visions “are different manifestations of an identical formula – that of dream control”.

In practice, modern devotees of the Necronomicon Current cultivate this oneiric aspect. They pay attention to their nightmares and fever dreams, fishing them for messages from the deep mind. They deliberately induce altered states—through meditation, drumming, or sometimes psychedelic “hyperchemistry”—to simulate the dream condition where the Outer Gods might speak. Mason notes that “the magic of the Necronomicon is based on dreams, visions and transmissions from planes and dimensions beyond the world as we know it”, and indeed many practitioners report that long before they performed a formal Lovecraftian ritual, they experienced a vivid dream of Dagon or heard the fluting of uncanny pipes in the twilight of sleep. The boundary between dreaming and wakeful ritual gradually thins. In these paths, one might say, the dream is the initiation. A seeker may undergo a harrowing inner adventure—beholding cryptic symbols, facing a monstrous figure in a lucid dream—and emerge with a changed soul, only later realising that was their initiation into the “Cult of Cthulhu” in a very real sense. The rational mind might balk, but the subconscious understands the pact that was made in that liminal space. Modern Lovecraftian magick embraces this dream-logic wholeheartedly, trusting that meaning often arrives shrouded in surreal allegory.

Terror as Catalyst, the Alien as Key

One of the most paradoxically empowering insights of these currents is that fear itself can be a tool of transcendence. Lovecraft famously wrote, “the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

Occultists in the Lovecraftian vein take this as a challenge: by deliberately confronting the unknown—the alien, the monstrous, the mind-shattering—they seek to transform that primal fear into a kind of sacred awe. In traditional myth cycles, the hero must face and overcome a dragon or descend into the underworld; the terror of that encounter is precisely what catalyses the hero’s metamorphosis. So, too, in Lovecraftian occultism: the practitioner becomes a kind of hero(ine) of their own weird tale, venturing into zones of terror with the aim not of succumbing but of emerging with expanded consciousness. The mythic function of terror here is to act as an initiatory crucible. When one stands in ritual and calls out to an entity like Azathoth—the “blind idiot Chaos at the center of infinity”—there is a very real moment of existential dread. Azathoth represents ultimate entropy and meaninglessness, a blind nuclear chaos where our sanity has no purchase. To invite such a presence is to stare into the abyss of nihilism and cosmic insignificance.

Yet, by doing so willfully and within a magical framework, the practitioner paradoxically gains power over that fear. It is no longer a nightmare one flees; it is a dragon one has ridden. The effect can be shattering and then illuminating. In the immediate aftermath, one might feel disoriented—“dislocated”, as Stone puts it—but that dislocation is precisely the point. It shakes loose the calcified perceptions of the self. For a moment, one experiences reality beyond the human comfort zone. And in that state, new insights flood in: perhaps a visceral understanding that the self is much smaller (or larger) than previously assumed, or a confrontation with the “great absence” that paradoxically reveals a hidden presence.

Many who work these rites report a kind of profound, wordless gnosis that arrives when the terror peaks and then breaks, like a wave. It’s as if touching the void makes one appreciate form and light anew, or conversely, as if embracing the darkness imparts a strange illumination. The alien in these workings serves as a mirror of the Other in ourselves. By facing the utterly alien, the practitioner recognises the parts of their own psyche and the universe that are alienated from ordinary awareness. The Outer Gods are so inhuman that they carry no baggage of earthly religion or dogma; they are blank canvases of the Beyond. Thus, to work with them is to court a perspective utterly outside the human. This can liberate one from all sorts of limitations—moral, psychological, even perceptual. In Lovecraft’s fiction, encountering the alien often drove characters mad because they had no framework to integrate the experience. However, in Lovecraftian occult praxis, one builds a framework (through myth, ritual, and philosophy) to incorporate that encounter productively. The terror becomes the trigger for a leap of consciousness. It forces the practitioner to evolve or break. With proper preparation, one evolves: the mind finds a way to expand around the incomprehensible, and in doing so, one’s old, small sense of self is transcended.

It is here that Kenneth Grant’s legacy particularly looms. Grant insisted that Lovecraft’s horror was, in fact, a gateway to deep truth—that the “evil” in Lovecraft’s stories was only our perception, and beyond it lay an amoral, cosmic truth waiting to be grasped.

To cross the abyss of fear and seeming evil was, for Grant, the task of the occultist. Mason and Stone, in their own ways, have taken up that mantle. Mason encourages the seeker to look past the grotesque masks of the “black gods” and find what wisdom or empowerment they offer once fear is mastered. Stone pushes the seeker to fling themselves into the cosmic maw and trust that some part of us will come out the other side, forever changed but wiser. In both, terror is not an endpoint but a means to an end: an engine driving the soul toward gnosis. It’s a delicate art to use such volatile fuel. Too much terror can traumatise or unhinge—but approached with respect and courage, it becomes transformative.

The mythic function of the alien here is similar. The alienness—the utter strangeness—of these Outer Gods is precisely what makes them powerful symbols of the Other. They represent that which is beyond human paradigms. In a sense, they are masks of the Ultimate Unknown. Engaging with them allows practitioners to grapple with the Unknown in a personal, intimate way. It’s one thing to intellectually say, “the universe is vast and we are tiny”; it’s another to ritualistically invoke a being that embodies that vastness and feel your own mind bow before its scale. The former is a fact; the latter is a revelation. By including the alien in our magical universe, we force our magical universe to expand. We invite in the element that forever keeps us on our toes, prevents stagnation, and guarantees that our practice is not just self-projection or comfort. The alien won’t conform to our ego’s demands—so it keeps us honest in seeking truth over convenience.

When The Stars Are Right

Thus, in these tentacled aeons, fear and strangeness themselves become sacred tools. The result is a body of occult work that is uniquely attuned to the zeitgeist of our time. We live in an era when classic certainties are dissolving, when humanity is peering deeper into a cosmos that offers no easy answers.

Lovecraft’s vision of an indifferent universe resonates strongly once again. But rather than succumbing to existential despair, the contemporary Lovecraftian occultist takes a bold approach: actively engaging that indifference and alienage and finding meaning on the far side of it. The terror becomes a teacher; the alien becomes an ally (or at least a reliable constant) in the search for meaning beyond the human sphere.

Fittingly, we now gather these threads in Black Stars in Dim Carcosa, an experiential journey that delves into these very mysteries. This series of essays has been a poetic and conceptual overture to that journey. This has been the third movement in this strange symphony, and its introspections lead us to the brink of practice.

Soon, theory and poetry will turn to lived experience. As the stars align on June 4th, 2025, the gates of the Black Stars in Dim Carcosa course will open, and a select cohort of seekers will step across the threshold. Like the fabled city of Carcosa itself, this portal is transient; the opportunity lasts until October 12th, 2025, when those gates are destined to close once more for good measure.

This is no just any date on a calendar, but a kind of appointed cosmic hour—it’s an invitation for dreamers and magicians to descend into the mythic underworld we have been mapping. The journey that awaits is, in a sense, an initiation on a collective scale: a chance to explore the Necronomicon Current through one’s own eyes and nerves, guided by the lineage of Grant, Simon, Mason, Stone and others, but ultimately forged in the personal crucible of each participant.

In undertaking that journey, we carry with us the insights gathered here. We acknowledge that the line between myth and reality is gossamer-thin, and that we ourselves play a role in thinning it. We have seen how fiction can become an egregore, how a dream can serve as a ritual, and how fear can fuel enlightenment. Standing at this threshold, one feels a sense of reverence and resolve. The unknown stretches out ahead, filled with nameless shapes and half-heard cosmic melodies. It is dark, yes, but not empty. It is alive with possibility.

The mythic function of what we are about to do is clear: we are reenacting the eternal human quest to wrest meaning from mystery. Only, in this incarnation, the mystery wears a tentacled mask and speaks in alien tongues. Yet, as we have learned, even the most alien gods can become doorways into the most intimate truths.

In the weeks to come, as participants of the course enter their dream circles and carry out their nightside workings, they will be doing so in the spirit of both currents we explored. They will use the imagination boldly, creatively, like Mason, and also surrender to experiences beyond the imagination, like Stone. They will walk with one foot in Carcosa and one foot in the Void. They will become, in a way, the dreamers in the void themselves—dreamers who dream with intention, who conjure and channel, who myth-make and thereby step into myth.

Tentacled Aeons as a concept captures the essence of this moment. It suggests that we are under the influence of vast and inhuman epochs of time and being—epochs symbolised by tentacled monstrosities from beyond the stars. It’s a poetic way of saying that a new spiritual current is emerging, one that is not clad in the familiar robes of familiar aeons (of Isis, Osiris, or Horus), but in the writhing form of something truly Other. We can sense this current in the culture: the resurgence of interest in cosmic horror, the blending of science fiction and spirituality, the way modern magicians look not just to ancient Egypt or Celtic lore for inspiration, but to the pages of weird fiction and the hypotheses of astrophysicists. The Tentacled Aeon is one where humanity begins to come to terms with the cosmic, the non-human, and the post-human. It is an era of both great anxiety and great wonder. And here, in our niche but meaningful exploration, we meet that era head on, with eyes open.

There is a certain beauty in this convergence of literature, imagination, and occult practice. It speaks to a larger truth: that all myths are born from the human attempt to interface with the Unknown. The Lovecraftian mythos is unusual only in that we know its precise author and date of origin—yet in a few generations it has acquired the same kind of numinosity that older mythologies have. This suggests that the capacity for the sacred is not reserved solely for ancient things. The sacred can arise wherever the human psyche, in its depth, invests attention and intention. In a way, we are watching in real time as a new “religion” (using the term loosely) takes shape. Not a religion with dogma or congregations, but a framework of meaningful symbols and rites that quite genuinely move people and produce results. It’s a testament to the creative power of consciousness.

And so we return to Lovecraft’s quote that we began with.

“We may think we’re writing fiction…and may even disbelieve what we write, but at bottom we are telling the truth…”.

Lovecraft, of course, meant it ironically, relaying someone else’s humorous theory. But in an elegant twist of fate, his words have become true in spite of themselves. The acolytes of Lovecraftian occultism are treating his fiction as a kind of truth—if not literal, then instrumental truth. The Outer Gods have become egregores; the Necronomicon has become a living idea with real power; the dreams of a pulp writer have become the seed of a hundred initiatory journeys. This is the magic of art and belief intertwined. It is the essence of the Tentacled Aeon: that we create our gods, and they, in turn, transform us.

With the course on the horizon, we are all invited to take part in this grand act of creation and transformation. The black stars are rising over dim Carcosa once more, and new voices will soon join the chorus of those “unwitting mouthpieces” of the Outside. Perhaps some of us, stepping into the ritual circle or the meditation chamber, will hear the faint piping of an otherworldly flute, or catch a glimpse of cyclopean cities in our mind’s eye. When that happens, we should remember that we stand at a crossroads of myth and reality. We are dreamers, yes, but also doers—magicians of the void as well as dreamers in the void. In that sense, the journey we embark on is both imaginative and very real. Through it, we affirm a profound, esoteric principle: that the act of imagination is itself initiatory. By imagining the Other, we invite the Other in; by mythologising our fears, we transmute them into gateways of insight.

Tentacled aeons surround us. The phrase need not inspire only dread; it can inspire wonder and humility. It reminds us that we are part of a cosmos vast and strange, and that the human adventure of consciousness is far from over—indeed, it may be only beginning anew on a higher turn of the spiral. As we conclude this reflective odyssey, we do so with a sense of anticipation. The curtain of the night is about to lift on a stage filled with black stars, eldritch truths, and the brave souls ready to encounter them. In that encounter lies the hope that each of us might wrest a spark of meaning from the madness, a pearl of wisdom from the abyssal sea. And if we do, we will carry forward the work of weaving the next chapter of this living myth—one more strand in the dark tapestry, glimmering like a distant star, to guide those who come after us through their own nights of fear and into the dawn of understanding.

Lovecraft’s legacy, filtered through occult experience, has taught us that even in the heart of darkness, there is something that calls to us—some promise of transformation. The tentacles of the Great Old Ones may be cold and alien, but they reach into the depths of our psyche, stirring it to life. As we answer that call, may we do so with respect, curiosity, and an abiding reverence for the grand mystery that lies both beyond us and within us. The journey continues, and the greatest revelation may yet be to find that the terror and the wonder were never truly separate to begin with. They are the twin faces of transcendence, beckoning us onward into the beckoning night of the soul.

Black Stars in Dim Carcosa begins June 4, 2025 – materials available until October 12, 2025. May our explorations be fruitful and strange.

STARS & SNAKES IS OUT NOW

I’m pleased to announce something new: the release of Stars & Snakes: A Thelemite’s Field Notes—a collected anthology of these very writings, gathered together in one volume under my own independent Chnoubis Imprint.