THE SATURNIAN ALLURE OF THE VAMPIRE

Unveiling the Real Occult Ties of Nosferatu

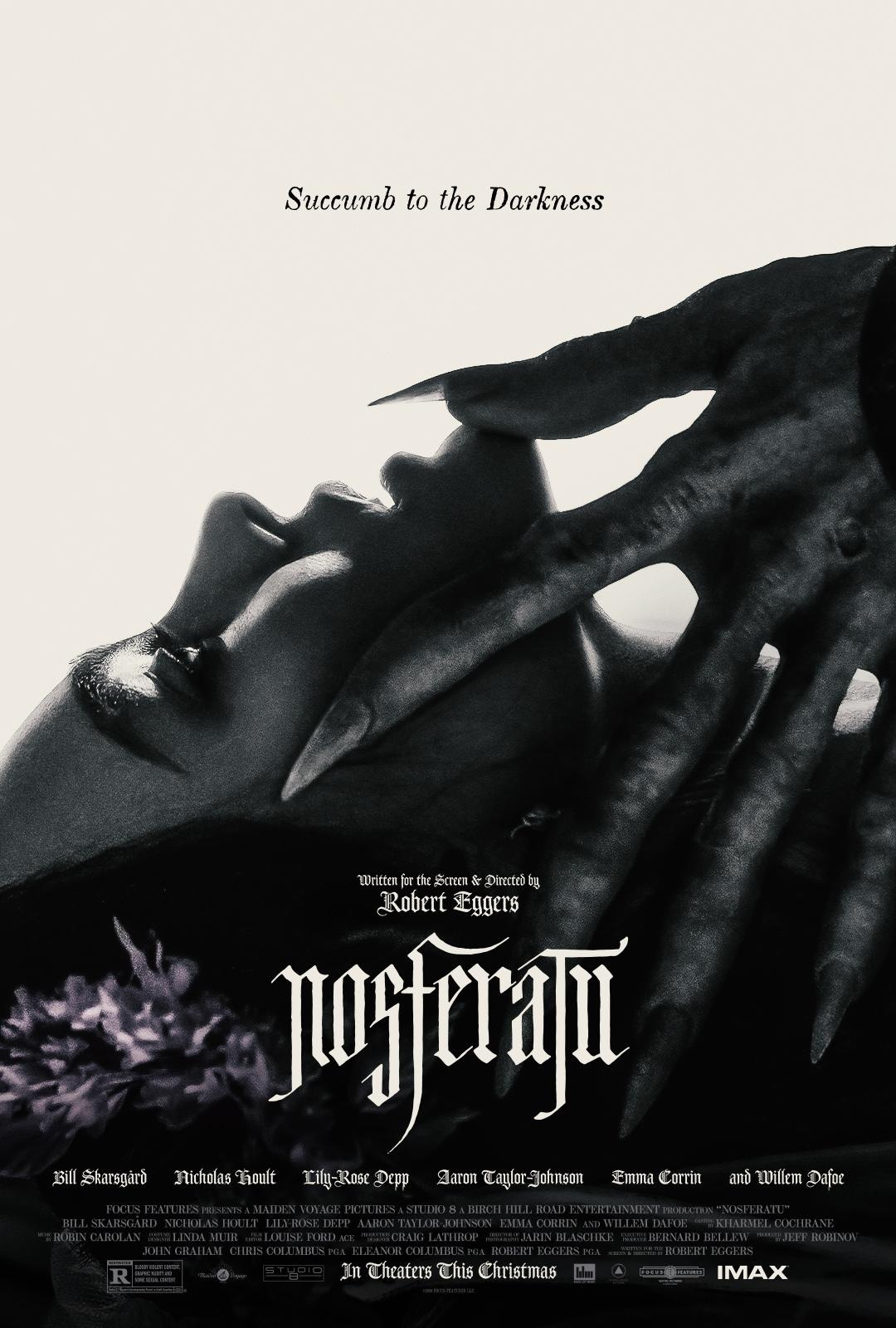

As Robert Eggers’ highly anticipated remake of Nosferatu captivates audiences, it casts a renewed light on the enduring power of the vampire myth. The film is replete with esoteric symbolism, but is there any genuine substance to what is seen on screen?

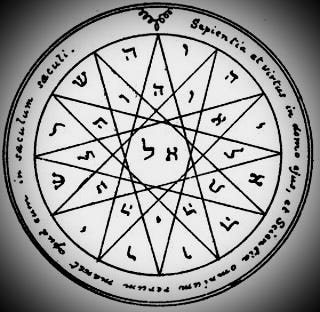

For example, the vampire seal seen in the movie is not an actual magical seal, just something that looks the part really well.

It does so because it is influenced by the conventional seals included in grimoires like the Ars Goetia and the Greater Key of Solomon.

Here, it seems that Eggers explicitly references the tale of the Solomonari, sorcerers in Romanian mythology reputed to ride a dragon and manipulate the weather, inducing rain, thunder, or hailstorms. The prevailing interpretation is that the term is linked to King Solomon by including the occupational suffix "-ar," but this may be folk etymology. And yet, I have little doubt this was the direct inspiration for the Nosferatu magical seal.

Another, even more famous vampire was a Solomonari himself. Bram Stoker wrote in Chapter 18th of his classic novel, Dracula:

The Draculas were, says Arminius, a great and noble race, though now and again were scions who were held by their coevals to have had dealings with the Evil One. They learned his secrets in the Scholomance, amongst the mountains over Lake Hermanstadt, where the devil claims the tenth scholar as his due.

And yet, the original Nosferatu was indeed steeped in genuine magical traditions.

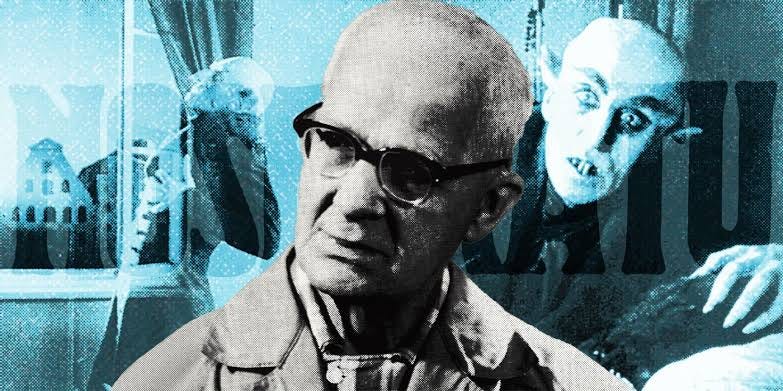

Central to the creation of the original 1922 film was Albin Grau, whose esoteric vision transformed Nosferatu into more than a horror classic—it became a mystical treatise on humanity’s confrontation with darkness, mortality, and spiritual transformation.

Grau’s ties to the Fraternitas Saturni (FS), a German magical order devoted to Saturnian doctrines, provided the foundation for his unique interpretation of the vampire archetype. This symbolic exploration starkly contrasts with the puritanical dread of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and aligns more closely with the work of occultist Kenneth Grant, whose writings extended the vampire myth into the realm of cosmic and preternatural forces.

Albin Grau: Artist, Occultist, and Visionary

Born in Germany in 1884, Albin Grau was a polymath whose life intersected the worlds of art, mysticism, and filmmaking. A lifelong student of the occult and a member of the Fraternitas Saturni under the magical name Master Pacitius, Grau infused Nosferatu with hermetic and mystical undertones. One striking example is the cryptic contract exchanged between Count Orlok and his servant Knock, which Grau adorned with Enochian, hermetic, and alchemical symbols, emphasising the film’s esoteric layers. Grau also shaped Orlok’s verminous and emaciated appearance, a haunting image that has endured as one of cinema’s most iconic depictions of the undead.

Grau claimed his inspiration for making a vampire film came during his service in the German Army in World War I when a Serbian farmer allegedly recounted that his father was a vampire—one of the Undead. While this story may have been a fabrication for promotional purposes, it reflects Grau’s deep engagement with folklore and the occult. Beyond his work in film, Grau was a prominent figure in esoteric circles.

He participated in the 1925 Weida Conference, an international gathering of occult leaders, where tensions between Heinrich Tränker’s Pansophic Lodge and Aleister Crowley’s Thelema led to a schism. Grau, along with Eugen Grosche (later Frater Gregorius), sided with those embracing Crowley’s Law of Thelema, which eventually resulted in the founding of the Fraternitas Saturni.

Despite his influence, Grau declined leadership roles within the FS, stepping down from the Master’s Chair of the Berlin Orient and leaving Grosche to guide the order into its Saturnian future. Grau instead focused on esoteric scholarship, contributing articles on sacred geometry—though often mathematically obscure—to the FS’s periodical Saturn Gnosis between 1928 and 1930.

His retreat from leadership did not diminish his impact; Grau’s contributions to both the FS and Nosferatu exemplify his lifelong commitment to exploring the esoteric dimensions of art and spirituality.

Grau’s involvement extended beyond the visual realm. He was also the driving force behind securing the film’s funding through Prana-Film, a production company he co-founded. Prana-Film was conceived as a studio dedicated to creating films with mystical and supernatural themes, with Nosferatu intended as its debut project. Although financial and legal troubles ultimately doomed Prana-Film, Nosferatu survives as a testament to Grau’s vision—a film that blends horror with the spiritual and the arcane.

The Puritanical Shadows of Stoker’s Dracula

Grau’s esoteric interpretation of the vampire diverged significantly from Bram Stoker’s portrayal in Dracula (1897). For Stoker, writing in the repressive Victorian era, the vampire represented a moral and spiritual aberration. Dracula was the ultimate predator, embodying forbidden sexuality, unholy immortality, and a defiance of Christian order. His predatory allure, particularly his effect on women, reflected deep-seated fears about the collapse of Victorian values. The Count’s ability to corrupt and seduce pure, virtuous women was a direct affront to the Protestant Christian ethos of the time, where moral virtue and sexual repression were closely intertwined.

Dracula’s overwhelming sexuality rendered him a terrifying figure, not only as a creature of the night but as a subversive force capable of undermining societal order. His victims, transformed into vampires themselves, became lascivious and insatiable, embodying everything Victorian society sought to repress. As Eszter Muskovits∗ notes, the act of vampiric bloodsucking was laden with sexual metaphor, representing an intimate, penetrative exchange that destabilised conventional gender norms. Dracula’s power to victimise women, turning them into beings who flaunted their desires and defied societal constraints, epitomised Victorian fears about the erosion of established gender roles. Lucy’s transformation into a vampire, for instance, marked her descent from the angelic ideal of womanhood into a predatory, overtly sexualised figure—an evident subversion of Victorian purity.

Beyond gender, the vampire’s transgressive nature extended into homoerotic undertones, especially in Dracula’s interactions with Jonathan Harker. The Count’s possessive declaration, “This man belongs to me,” carried implicit connotations of same-sex desire, unsettling a culture that viewed deviations from heterosexual norms as chaos and moral disorder. Furthermore, the "Crew of Light," the band of vampire hunters, could be seen as an attempt to reassert patriarchal control and restore societal order. Their transfusion of blood to Lucy, a process charged with symbolic exchange akin to sexual fluidity, highlighted anxieties about male dominance being diluted or threatened by Dracula's intrusion.

For Stoker, the vampire was a symbol of absolute evil, a creature whose existence threatened the moral and spiritual fabric of society. Its eradication by a group of righteous men symbolised not just a victory over an external predator but a restoration of Victorian order, gender roles, and Christian virtue. Through the lens of Stoker’s Dracula, the vampire becomes an enduring metaphor for the tensions and fears of a society grappling with the shadows of its repressed desires and anxieties.

Grau’s Esoteric Vision and the Saturnian Doctrine

In contrast to Stoker’s moralistic lens, Grau saw the vampire as a far more complex figure, tied to spiritual and psychic archetypes. Influenced by the Saturnian teachings of the Fraternitas Saturni, Grau reinterpreted the vampire as a symbol of transformation through confrontation with darkness. Saturn, in esoteric tradition, represents restriction, death, and rebirth—the forces that initiate profound spiritual change. Grau viewed the vampire as a reflection of these principles, a shadowy force that compels the aspirant to face mortality, fear, and their own inner darkness.

But there is more. As the planetary ruler of Aquarius, Saturn is also believed to fuel the much-anticipated Age of Aquarius, an era of collective awakening and innovation. Grau viewed the vampire as a reflection of these principles, a shadowy force that compels the aspirant to face mortality, fear, and their own inner darkness.

In Nosferatu, Count Orlok transcends his role as a predator to become a metaphysical figure. His grotesque, rat-like visage and his parasitic hunger evoke not only horror but existential reflection. Orlok, like Saturn, disrupts and challenges, serving as both a destroyer and a potential guide. This duality aligns with the FS’s concept of GOTOS, the egregore that embodies the collective psychic energy of its members.

An egregore is a metaphysical construct sustained by the rituals and intentions of a group. GOTOS, central to the FS’s doctrines, served as both a reservoir of collective will and a force that tested its creators.

The vampire archetype mirrors this role: it sustains itself through predation yet serves a higher symbolic purpose by forcing those it encounters to confront their own limitations and mortality. Grau’s vision of the vampire, steeped in these esoteric ideas, makes Nosferatu a cinematic expression of Saturnian initiation.

Kenneth Grant and the Cosmic Vampire

Grau’s interpretation of the vampire finds a fascinating parallel in the work of British occultist Kenneth Grant. A disciple of Aleister Crowley, Grant extended the vampire mythos into the realm of cosmic and magical forces through his Typhonian Trilogies. For Grant, the vampire was not merely a folkloric creature but a symbol of humanity’s engagement with primordial and extraterrestrial energies. His writings suggest that the vampire embodies connections to alien intelligences, forbidden knowledge, and the liminal spaces of existence.

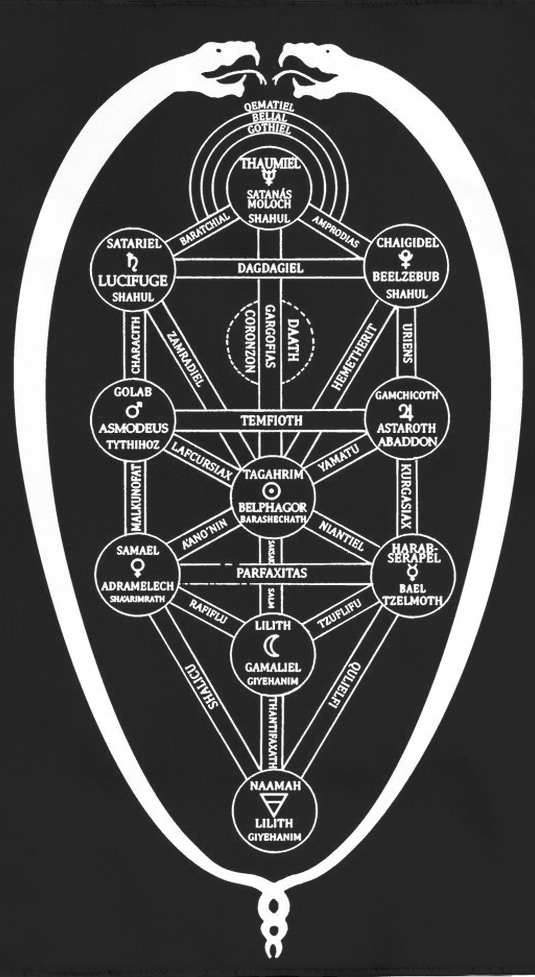

For Grant, the vampire was an emissary of the “Nightside,” a term he used to describe the shadowy, subconscious realms of experience and magical practice. In his writings, he frequently invoked the Qliphoth, the dark, chaotic inverse of the Tree of Life in Qabalistic tradition, as the source of the vampiric force. The Qliphothic spheres, including Gamaliel, represented realms of shadow and disintegration that paradoxically held the potential for profound spiritual transformation. Within this framework, the vampire served as a liminal figure—a mediator between the conscious and unconscious, the human and the alien, the terrestrial and the cosmic.

While Grant invited exploration of the “other” side and sought to re-establish the divine feminine as a necessary counterbalance to Crowley’s insistence on Thelema as a “solar-phallic” current, he reframed the mystical paradigm as “stellar”—aligned with the vast and unknowable—making the feminine cosmic and “other” by nature. This reframing placed the vampire in a liminal, almost sacred role as an initiatory force. In Grant’s cosmology, the vampire became an avatar of the repressed feminine, tied to lunar and stellar mysteries, which held keys to both empowerment and annihilation. The consuming nature of the vampire, symbolised by its thirst for blood, mirrored the psychic demands of the Nightside paths, which draw practitioners into transformative, often destructive, encounters with their own shadows.

Yet, for all his visionary ideas, Grant betrayed his innate Britishness by continuing to see the vampire as something to be feared, even while recognising its transformative potential. “The vampire force is a very real one, and one which operates today as of old in most insidious and unsuspected ways,” he warned, underscoring the ambivalence with which he regarded these forces. While he encouraged occultists to engage with the Nightside, his cautionary tone reflected the inherent risks of such explorations: the loss of individuality, psychic dissolution, and the lure of becoming trapped in destructive cycles of desire and fear.

This ambivalence is particularly evident in one of his Typhonian narratives, Gamaliel: The Diary of a Vampire.

The story follows a woman named Vilma who descends into an obsessive relationship with the entities of Gamaliel, the Qliphothic sphere associated with the dark side of the Moon. In the diary, Vilma is consumed by her yearning for connection to higher—and darker—forces. Her interactions with the vampiric entities of Gamaliel reflect both her aspirations to transcend human limitations and her descent into a vortex of madness, hallucination, and alien insight. The “vampire” here is not a physical creature but an energetic and psychological force that feeds on Vilma’s vitality and sanity, luring her deeper into the mysteries of the Qliphoth.

“The vampire force is a very real one, and one which operates today as of old in most insidious and unsuspected ways.

Kenneth Grant in “The Carfax Monographs” (1959–1963)

Vilma’s journey is emblematic of the broader themes in the Typhonian tradition: the confrontation with alien forces that disrupt conventional understandings of identity, morality, and reality. The vampire, as a symbol of the Qliphoth, compels humanity to confront its fears and desires, acting as both a destroyer and an initiator. The narrative echoes Grant’s larger occult philosophy, in which the seeker must navigate a perilous path through the Nightside, balancing the allure of cosmic power against the risks of dissolution and madness.

In Grant’s Typhonian tradition, as in Grau’s cinematic vision, the vampire is a liminal figure that compels humanity to confront its fears and desires. However, Grant’s portrayal reveals the tension between embracing the “other” as a source of transformative power and recoiling from its alien, unsettling nature. This duality underscores the vampire’s enduring complexity as an archetype of both terror and initiation.

Ultimately, Grant’s cosmic vampire is not simply a predator or a symbol of death; it is an agent of profound change, demanding that the individual confront the unknown within and beyond themselves.

A Legacy in the New Aeon

Eggers’ reinterpretation of Nosferatu offers an opportunity to re-examine the vampire’s evolution as an archetype. From Stoker’s embodiment of Victorian moral panic to Grau’s esoteric reinterpretation and Grant’s cosmic lens, the vampire remains a figure of fascination and complexity. Each era reshapes the myth to reflect its anxieties, aspirations, and spiritual struggles.

Through the visions of Grau and Grant, we see the vampire as an enduring symbol of the aspirant’s struggle with mortality, limitation, and transformation.

Nosferatu emerges not only as a landmark in cinematic history but as a profound meditation on the human condition, where darkness and desire serve as pathways to enlightenment.

In Grau’s hands, the vampire ceases to be a simple monster and becomes a mirror of our own shadow—a symbol of the trials we must endure to complete the Alchemy of the Great Work.

Great post, Marco! Honestly, I haven’t read Grant since my early 20s…it might be time to reread him with better understanding based on the decades of the Work that lay between early 20s me and late 40s me.

Enjoyed this post. Thank you for bringing up different connections than I did when analyzing the film! (: