Aleister Crowley’s Holy Books of Thelema are a collection of mystical writings regarded as sacred scripture within the religion-philosophy of Thelema.

These texts, designated “Class A” in Crowley’s system of classification, occupy a unique and exalted place in Thelemic mysticism. They are believed to be inspired works, written not by Crowley so much as through him, and thus “not to be changed, even to the letter”. For newcomers to Thelema, the Holy Books serve as both foundational mythos and practical guide, illuminating the path of spiritual attainment that Crowley’s system advocates. This introductory article will explore the historical and esoteric genesis of these Class A texts, their classification and purpose, and their importance within Thelemic mysticism.

In doing so, we will also discuss key themes such as the mode of revelation and automatic writing through which they were produced. Comparative references to other mystical traditions will be included to help place these Thelemic concepts in context, though our primary focus remains on Thelema’s own complex and transformative tradition.

As with the previous one, this article is born of a promise I made long ago to my friend Dr Justin Sledge (of ESOTERICA YouTube Channel fame). If you haven’t yet, you can read the introduction to The Vision And The Voice below.

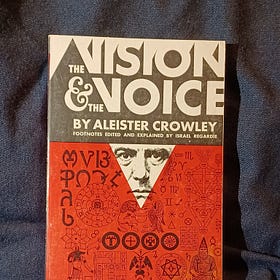

ALEISTER CROWLEY'S "THE VISION AND THE VOICE": AN INTRODUCTION

Aleister Crowley’s The Vision and the Voice (technically titled Liber XXX Aerum vel Saeculi sub figura CCCCXVIII) is a seminal work in the Thelemic canon, and in my personal opinion second only to Liber AL vel Legis in importance.

Origins of the Holy Books and Their Revelation

The genesis of the Holy Books of Thelema is rooted in Crowley’s mystical experiences in the early 20th century. The first and most famous of these texts, Liber AL vel Legis (also known as The Book of the Law), was received in Cairo in 1904 under dramatic circumstances.

Most of my readers will already be familiar with this story. Still, for the few who just stumbled here by chance, it goes as follows: Crowley recounted that a disembodied voice, identified as Aiwass, dictated the text to him over three days. He described the experience as if an actual voice spoke in his ear, compelling him to write even when he tried to stop.

At first, Crowley thought this might be an “excellent example of automatic writing”, but he later insisted it was more than that – a direct transmission from a praeter-human intelligence. Crowley was so struck by this experience that he disclaimed authorship of The Book of the Law “not with [his] littlest finger-tip”, distinguishing it from his other inspired writings. This text declared the dawn of a new spiritual era (the Aeon of Horus) and set forth Thelema’s central tenets: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” and “Love is the law, love under will.”

In the years that followed, Crowley experienced a torrent of revelatory writings. Beginning in 1907, he produced numerous additional Class A texts in rapid succession. These came to him in states of heightened consciousness – through trance, meditation, or other altered states – and he claimed they were dictated by divine or higher astral beings, or by his own Holy Guardian Angel. For example, Liber VII: Liber Liberi vel Lapidis Lazuli was “revealed” to Crowley in 1907 as the first Holy Book after The Book of the Law, marking the start of this inspired literary outpouring. Likewise, Liber LXV: Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente and others soon followed, primarily between 1907 and 1911. Crowley later reflected on this period, saying he was “inspired beyond all I know to be I” in writing these Class A books. He viewed himself as a scribe or medium, channeling exalted knowledge that came from an Adept or spiritual source beyond critique, rather than composing the texts purely from his conscious mind.

The mode of writing for many Holy Books can be described as automatic writing or visionary dictation. Crowley would often sit and write in a single sustained burst, sometimes under specific ritual conditions. In some cases, he reported that if he tried to alter or hesitate with the wording, an unseen force urged him on.

This method is comparable to the revelatory scripture in other traditions – for instance, the prophet of a new religion taking dictation from an angel or divine voice (one might compare Crowley’s Aiwass to Joseph Smith’s Angel Moroni or Muhammad’s Angel Gabriel, in terms of delivering scripture).

However, Crowley’s revelations were distinct in style: highly symbolic, poetic, and often cryptic, requiring interpretation. He believed the Holy Books of Thelema carried coded spiritual truths and magical formulae that could guide aspirants on the path of enlightenment, provided one meditated on them deeply.

Classification and Purpose

Crowley devised a system to classify the publications of his occult orders (the A∴A∴ and the O.T.O.), dividing writings into categories A through E. The Class A designation is reserved exclusively for the Holy Books – texts that, in Crowley’s words, “may not be changed, not so much as the style of a letter”. This means that Class A texts are to be taken as received wisdom; they represent, as Crowley put it, the “utterance of an Adept entirely beyond the criticism of even the Visible Head of the Organization.” In other words, not even Crowley himself (as the head of the A∴A∴) could alter a comma of these works, since they were considered perfect transmissions from a divine or superhuman source. This contrasts with Class B documents (which are enlightened works of scholarship or philosophy by Crowley and others), Class C (suggestive material or speculation), Class D (official rituals and instructions), and Class E (pronouncements or propaganda). By marking a text as Class A, Crowley signalled to his students that “here is sacred ground”, and these writings function as the scriptural core of Thelema, to be revered and studied for insight, rather than analysed or modified in a purely intellectual manner.

What is the purpose of these Holy Books? Broadly, they serve to inspire and initiate. Each Class A text reveals some aspect of Thelema’s cosmology, mystical path, or magical formulae through exalted poetry and symbolism. Crowley intended them to encapsulate the stages of the spiritual journey he outlined for aspirants.

They are not textbooks in a conventional sense; rather than instruct via plain language, they stimulate the soul through paradox, imagery, and allegory. He likened some of these works to cryptograms that the aspirant must decipher in the light of their own intuition and experience, emphasising personal understanding over dogmatic reading.

The Class A Texts of Thelema

Below is a concise survey of each of the Holy Books of Thelema, one-page sketches that highlight their role, themes, and style, with one important exception: Liber AL vel Legis itself demands its own full exegesis and the fortitude to become a centre of pestilence. I warmly embrace that challenge, yet I must confess I am not yet prepared to undertake so vast, and potentially disruptive, an ordeal.

Liber B vel Magi, sub Figura I

Role in Thelema: Liber B is an account of the Grade of Magus – the loftiest attainable grade in the A∴A∴ initiatory system. In Thelema, the Magus (grade 9°=2□) is one who has attained ultimate mastery and declares a Word that transforms the world’s spiritual evolution. This book thus outlines, in symbolic form, the nature of that exalted office.

Major Themes: The key theme is Truth veiled in Illusion. The text famously begins: “In the beginning doth the Magus speak Truth, and send forth Illusion and Falsehood to enslave the soul.” This paradox suggests that a Magus, in uttering divine Truth, must necessarily cast it into forms that lesser minds can grasp, which may appear as illusion or doctrine. Crowley implies that the Magus’s Word is true on a cosmic level, yet it spawns creeds and dogmas (partial truths or “illusions”) as it filters down into human understanding. Another theme is the duality of the Magus’s role: he is at once a creator and a destroyer of illusion, a teacher who must sometimes mislead to ultimately liberate. Implicitly, Crowley is also commenting on his own mission as Magus of the New Aeon, whose Word Thelema would inevitably be misunderstood or distorted by followers.

Style and Symbolism:Liber Bis brief (only a couple of pages) and is composed in a terse, aphoristic style. It reads like a series of cryptic pronouncements or axioms about the Magus. The language is exalted but abstract, requiring contemplation to unravel its meaning. There is a tension between Silence and Speech running through the text — a Magus must remain silent (hidden) about his true nature while his Word speaks loudly to the world. Crowley originally classified Liber B as a Class B essay, but in 1913 he elevated it to Class A, indicating he came to regard it as a product of inspiration rather than an ordinary composition. Symbolically, the title “B vel Magi” hints at Bêth, the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet (associated with the Magus card in Tarot), underscoring the creative Word (Logos) aspect of the Magus. Overall, this little book serves as a concise portrait of enlightened attainment at the highest level, delivered with the mysterious authority of one who has attained that summit.

Liber Liberi vel Lapidis Lazuli, sub Figura VII

Role in Thelema: Liber Liberi vel Lapidis Lazuli is one of the most revered Holy Books, regarded by Crowley as a masterpiece of inspired writing. It is “given to Neophytes” (the 1°=10□ grade) in the A∴A∴ system as preparation for the knowledge of a Master of the Temple. In other words, this text serves to inspire aspirants with a vision of the exalted state of the Master of the Temple (8°=3□) – the grade above the Abyss. Crowley described the text as “the birth words of a Master of the Temple”, suggesting it captures the ecstatic utterances of an Adept who has surrendered the ego and crossed into true spiritual adulthood.

Major Themes: The overarching theme is Mystical Union through Surrender. Across its seven chapters, Liber Liberi depicts the soul of an Adept undergoing a voluntary obliteration of personal identity to merge with the divine. There are intense images of spiritual death and rebirth, sexual mysticism, and rapturous love for the divine (often using the imagery of Babalon as the beloved). The text is suffused with poetic visions of inebriation – “drunkenness” on the wine of ecstasy – and passages of radical self-abandonment. This reflects the journey of the Exempt Adept (7°=4□) relinquishing all to cross the Abyss and be reborn as a Master of the Temple. Each chapter is associated with one of the seven classical planets (albeit not in any of the classic sequences - from Luna to Saturn or viceversa), giving the work a cosmic scope: from the warlike passion of Mars to the dreamy love of Venus, the Adept’s experience encompasses the entire spectrum of existence. The tone moves from agonised yearning to sublime fulfilment as the aspirant achieves union with the All.

Style and Reception:Liber VII is written in highly charged free verse. The language is lush, passionate, and at times deliberately scandalous or shocking in its sacred erotism, reflecting Crowley’s view that divine union transcends conventional morality. The title Liber Liberi (Book of the Free One) hints at liberation, while Lapidis Lazuli (Lapis Lazuli stone) symbolises spiritual treasure or the sapphire stone of the celestial palace. Crowley penned the entire 5,700-word text in one overnight session on October 30, 1907, in a state of trance or samadhi, writing “without a single moment’s pause”. He later marvelled that the result possesses a sustained poetic grandeur that he “was totally incapable” of in normal consciousness. Indeed, Crowley held Liber VII in the highest esteem, pairing it with Liber LXV as a text of unparalleled sublimity among the Holy Books. For the Thelemite devotee, Liber VIIprovides a sweeping and inspirational glimpse of the promised land of mystical attainment and the state of oneness and divine intoxication that lies at the culmination of the path.

Liber Porta Lucis, sub Figura X

Role in Thelema: Liber Porta Lucis (“The Gate of Light”) is an instructional piece directed toward those who have attained mastery and are sent forth to teach mankind. In the A∴A∴ tradition, it is described as “an account of the sending forth of the Master by the A∴A∴ and an explanation of his mission.”. Essentially, this text outlines the role and duty of a Master of the Temple (or one who has achieved enlightenment) to serve as a guide for others on the path. It can be seen as Crowley’s mission statement for enlightened teachers in the Aeon of Horus, and an attempt to clarify what a true Thelemic master is supposed to do in the world after attaining the Knowledge of the Light.

Major Themes: The primary theme is the Great Commission of the Adept. The text speaks in the voice of an enlightened authority delivering a message to humanity. It emphasises illumination, that is the bringing Light (spiritual understanding) to those who dwell in darkness or ignorance. The “Gate of Light” implies a portal through which the adept emerges, bearing the lamp of gnosis for others. Another theme is responsibility: with great attainment comes the responsibility to “explain his mission” and deliver the Law of Thelema to the world. The work implicitly touches on selflessness as well; even after achieving unity with the divine, the Master returns to serve the universe (echoing the Bodhisattva ideal in Buddhism).

Style and Symbolism:Liber X is relatively short and written in a clear yet elevated prose style. It reads almost like a communiqué or manifesto. Crowley received it on December 12, 1907, likely in a meditative state. The title “Porta Lucis” alludes to a classical Rosicrucian text of the same name, connecting Crowley’s work to earlier Western esoteric tradition. Symbolically, the “Gate of Light” may represent the transition from the inner planes (where the adept attained enlightenment) back into the outer world of form. We might picture the Master Therion (Crowley’s title for himself as a Magus) stepping out through this portal, tasked by the Secret Chiefs or the A∴A∴ to spread the new Law. In tone, Liber Porta Lucis carries a mix of solemn authority and compassionate outreach, and it is at once a decree and an invitation, calling readers to seek the Light that the Master is unveiling. For students of Thelema, this little book serves as a reminder that the path of attainment does not end with personal bliss; it expands outward as spiritual service to humanity, in alignment with the will of the Masters of Wisdom.

Liber Trigrammaton, sub Figura XXVII

Role in Thelema: Liber Trigrammaton is a cryptographic holy book that serves as a kind of cosmological blueprint in the Thelemic corpus. It is “a book of Trigrams of the Mutations of the Tao with the Yin and the Yang”, intended to be an account of the cosmic process. Crowley assigned Liber XXVII to the grade of Practicus (3°=8□) in the A∴A∴, saying that it contains “the ultimate foundation of the highest theoretical Qabalah.”. In practical terms, this means the book is used as a tool for advanced students to study the fundamental patterns underlying reality, much as one might study the I Ching or the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. Its role is somewhat analogous to scripture like the Stanzas of Dzyan in Theosophy in providing a symbolic genesis of the universe that the adept can meditate upon to gain insight into metaphysical truths.

Major Themes: The central theme is Creation as a Dynamic of Dualities. Liber Trigrammaton presents a series of 27 trigrams (three-line symbols) which combine broken and unbroken lines. Through these elemental symbols, the book depicts the progressive emanation of the cosmos from unity into multiplicity. Each trigram, accompanied by a brief text or number, can be read as a stage in creation where the interplay of active (yang) and passive (yin) forces gives rise to phenomena. There is a profound emptiness and fullness motif, echoing the Taoist idea of the Tao producing the One, the One producing the Two, and so on. The text implies a cyclical or mutational view of reality: existence is a continual flow of changes governed by a primal duality (which Thelema might interpret as the interplay of Hadit and Nuit, the cosmic masculine and feminine). Another theme is silence beyond thought: because Liber Trigrammaton is nearly wordless (being mostly symbols and numbers), it forces the aspirant to quiet the mind and intuit the meaning beyond rational concepts.

Style and Symbolism: This text is highly abstruse in form. It consists of symbolic diagrams rather than narrative or poetry. The accompanying verses are extremely terse, sometimes just a few words or a riddle-like phrase. The overall style is gnomic and oracular, and it feels ancient, cryptic, and impersonal. Crowley noted that Liber XXVII was received on 14 December 1907, likely during trance; notably, no changes were ever made, emphasising its status as a pure, untouched cypher. Symbolically, the number 27 (3 time 3) suggests completeness in creation (3 planes: physical, mental, spiritual, each divided into 3, etc.), and the trigrams can be mapped onto various esoteric systems (Tarot trumps, Hebrew letters, elements, etc.) for interpretation. For a Thelemic practitioner, meditating on Liber Trigrammatoncan be a profound exercise in Qabalistic analysis, teasing out the universal laws encoded in the interaction of opposites that give birth to the manifest universe. It is perhaps the most austere and conceptually challenging of the holy books, rewarding the Practicus with deep insight into the architecture of reality when its symbols finally begin to speak in the silence of the soul.

Liber XXXI (Holograph Manuscript of Liber AL vel Legis)

Role in Thelema: Liber XXXI is not a separate doctrinal text, but the precious manuscript of Crowley’s most important revelation, Liber AL vel Legis (The Book of the Law). In accordance with instructions given within The Book of the Law itself, Crowley considered the exact handwritten form of the text to be sacrosanct and laden with hidden meaning. He appended the facsimile of the original 1904 manuscript as Liber XXXI in published editions, ensuring that students could inspect the “chance shape of the letters” for any mysteries beyond the literal words. The role of Liber XXXI, then, is to preserve the revelation in its original form, serving as a kind of scripture reliquary. It is often bound together with Liber CCXX (the typeset version) so that the two may be compared line by line.

Major Themes/Insights: Since Liber XXXI is The Book of the Law in content, its themes are identical to Liber CCXX – the proclamation of the Law of Thelema, the advent of the Aeon of Horus, and the mystical teachings of the deities Nuit, Hadit, and Ra-Hoor-Khuit. However, Liber XXXI carries an extra layer of significance in that it underscores the importance of literal detail and orthography in revelation. The presence of this manuscript emphasises continuity and authenticity: it is the tangible artifact of Aiwass’s dictation. Students examining Liber XXXI have noted curious anomalies, such as the missing chapter number in Chapter I, unexplained marks or “fill in the blank” words, which Crowley believed might themselves be riddles posed by the Secret Chiefs. Thus, a theme one could ascribe to Liber XXXI is the Mystery of Revelation itself. It invites reverence for the raw moment of communication from the divine and encourages seekers to look between the lines (and letters) for occult truths.

Style and Reception: The style is that of a prophetic utterance in three chapters, but here one encounters it with all the original quirks of penmanship: deletions, insertions, and even a phrase added in another hand (Crowley’s wife Rose penciled in an omitted line at one point, under Aiwass’s direction). The visual impression of the manuscript – for example, the stele hieroglyph drawings in the margins, or the bold signatures of the praeter-human communicator at the end of each chapter – adds a mythic, tactile quality to the experience of the text. Crowley insisted on reproducing the manuscript in all future printings ofThe Book of the Law, a directive rooted in verses of Liber AL itself (III:39 and III:47) which stress preserving the manuscript “for in it is the secret word” and the value of even the “chance shape” of letters. Essentially, Liber XXXI functions as a holy relic in Thelema: it is the unaltered raw transmission of the new Aeon, to be treated with the same veneration one might give the original tablets of an ancient scripture.

Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente, sub Figura LXV

Role in Thelema: Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente, meaning “The Book of the Heart Girt with a Serpent,” is a central mystical text of Thelema. It is “an account of the relations of the Aspirant with his Holy Guardian Angel.” Crowley intended Liber LXV especially for Probationers (the entry-level grade in A∴A∴) as a preparation and inspiration for the primary task of the Outer Order: achieving the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel. In the A∴A∴ scheme, this attainment is considered the “Crown” of the first order – the moment when the adept truly contacts their divine self. Thus, the role of Liber LXV is to guide and encourage aspirants in this Great Work, using poetic and symbolic narratives to illustrate the soul’s evolving relationship with its divine genius.

Major Themes: The main theme is the lover-beloved relationship between the human soul and its Holy Guardian Angel. Across five chapters, the text depicts the Aspirant (often voiced in the first person) in a passionate, sometimes tumultuous dialogue with the Angel (referred to in lofty, endearing terms). This is essentially a spiritual love song or mystical diary of one seeking union with the divine beloved. Themes of ecstasy and despair alternate as the Aspirant experiences closeness with the Angel in one moment and feels abandoned or unworthy in the next, mirroring the very real psychological trials of the path. Another key theme is purification through suffering: the Aspirant’s heart (encircled by the serpent of divine wisdom) endures ordeals and temptations, yet each trial refines his understanding and devotion. The book is rife with alchemical and religious imagery (cups of wine, serpents, gardens, blood, and roses) symbolising the stages of inner transformation. Finally, when union is achieved, the theme shifts to transcendent unity – “I am Thou and Thou art I,” an utterance of identity with the Angel that crowns the work. Notably, Crowley considered Liber LXV one of the “chief” holy books for its sublime portrayal of enlightenment.

Style and Symbolism:Liber LXV is written in a rich, lyrical prose/verse that often reads like scripture or Song of Songs-style poetry. The title evokes the image of a serpent coiled around the heart, which is a potent symbol: the serpent represents divine wisdom or Kundalini force, and the heart is the core of the soul – their union signifies enlightenment through love. Each chapter of LXV has its own tone: for example, Chapter I opens with a creation myth atmosphere and the Angel’s voice calling the Aspirant; Chapter II includes a parable of the garden (echoing the Garden of Eden, but with Thelemic twists); Chapter III and IV intensify the dialogue and the Aspirant’s trials; Chapter V concludes with profound unity and peace. Crowley wrote Liber LXV in late October and early November 1907, notably right after finishing Liber VII. Unlike the one-sitting reception of Liber VII, Liber LXV came “a chapter or two at a time” over several nights, perhaps reflecting its structurally sequential journey from first invocation to final attainment. The style is highly figurative and symbolic: one finds references to biblical motifs, Qabalistic sephiroth, and Thelemic allegories (the “City of the Pyramids” appears as a vision of the supernal realm). For readers, Liber LXV offers a deeply moving and personal guide to communion with the divine. Its verses are often memorised or used in ritual by Thelemites as affirmations of their own spiritual relationship with the Holy Guardian Angel. In sum, this Holy Book stands as a poetic blueprint of illumination, mapping the ardent courtship between the aspiring soul and the indwelling divine spark that leads to consummation in the eternal beloved.

Liber Stellae Rubeae, sub Figura LXVI

Role in Thelema: Liber Stellae Rubeae (“The Book of the Ruby Star”) is a short but intensely cryptic text that functions as a secret ritual instruction within the Thelemic canon. Crowley’s note describes it as “A secret ritual, the Heart of IAO-OAI, delivered unto V.V.V.V.V. for his use in a certain matter of Liber Legis”. Here V.V.V.V.V. refers to Crowley’s mystical title as a Master of the Temple, as well as the Chief Adept of the A∴A∴, and it stands for Vi Veri Universum Vivus Vici, with the U of Universum rendered as V following the Latin script. The role of Liber LXVI is thus to convey an occult ritual formula linked to Liber AL vel Legis, presumably to be employed by the adept (Crowley or others of similar grade) to accomplish a particular magical aim. It is considered “secret” in the sense that its true operative meaning is veiled; Crowley did not openly elucidate it in his curriculum, implying it’s meant to be deciphered only by those with sufficient insight or initiation.

Major Themes: The content of Liber LXVI is highly symbolic and couched in sexual-alchemical imagery. The major theme is sacred sexuality as a sacrament – the “Heart of IAO” refers to the formula IAO, a well-known Gnostic magical formula of death and resurrection (corresponding to Isis, Apophis, Osiris). By writing it also as O.A.I., the text hints at a reversed or mirrored formula, suggesting the interplay of masculine and feminine creative energies. Thus, one theme is the union of opposites (the union of the magician and his Scarlet Woman perhaps, or the conjoining of divine masculine and feminine). The “Ruby Star” itself symbolises a menstruum or divine blood, and is likely a reference to the “Blood of the Red Grail”, which in Thelemic mysticism is the menstrual blood or sexual fluids offered to Babalon. In fact, though Babalon is not named explicitly, the concept of the Scarlet Woman (Ruby = red, Star = Venus or Babalon as celestial goddess) underpins the text. The ritual described (obliquely) in this book involves sacrifice and ecstatic union: offering one’s life force or “blood” into the Cup of the divine feminine, which is a formula for crossing the Abyss (similar to Liber Cheth’s theme). Another theme is silence and secrecy, and at the end, the text enjoins the practitioner to keep silence about the ritual, underscoring its initiatory nature.

Style and Symbolism:Liber LXVI is written in an ecstatic, prophetic prose that is fragmented and riddling. It features a series of invocations and declarations in a style that borders on the liturgical. The imagery is vivid and often sexual: it speaks of “rose” and “wine” and uses the language of sacrament and consummation. Because Crowley links it to “a certain matter of Liber Legis,” readers have speculated that it relates to specific verses in The Book of the Lawthat required a ritual implementation (possibly something to do with Chapter III’s war and vengeance formulas, or with the establishment of the rites of the new Aeon). The phrase “Heart of IAO-OAI” is itself symbolic: IAO in Thelemic magick can correspond to the process of Solve et Coagula (dissolution and coagulation), and the heart of it implies going to the very core of the formula. Received on November 25, 1907, the text carries the intense energy of that creative period. It is “sufficiently described by the title,” Crowley notes wryly, suggesting one must meditate on Stellae Rubeae to intuit its full import. Stylistically, Liber LXVI reads as if it were the transcription of a vivid vision or the litany of a priest in the throes of invocation. To the uninitiated, it might appear as nonsensical or scandalous verses, but to a Thelemite adept, it provides a formula for unlocking a deep mystery of Liber AL, through the holy act of a secret ritual uniting the microcosm and macrocosm in the field of the Ruby Star.

Liber Tzaddi vel Hamus Hermeticus, sub Figura XC

Role in Thelema: Liber Tzaddi vel Hamus Hermeticus functions as an enigmatic invitation to initiation. Crowley summarised it as “an account of Initiation, and an indication as to those who are suitable for the same.”. In other words, it is written in the voice of an enlightened master offering guidance (and a challenge) to aspirants who would follow the Hermetic path. The term “Hamus Hermeticus” means “the Hermetic Fish-hook,” an image that implies hooking or drawing in the true seekers while letting the unworthy slip away. The role of Liber Tzaddi in the Thelemic corpus is somewhat akin to a manifesto or recruitment tract for the path of occult initiation, but couched in lofty, allegorical language.

Major Themes: The key theme is the call of the Master to the disciple. It presents a sequence of declarations from an adept (possibly an embodiment of an inner-plane guide) who implores the reader to “follow me” along the path of wisdom, yet warns of the trials and solitude it entails. There is an undercurrent of elitism vs. universality: the text speaks both inclusively and exclusively — anyone may attempt the path, but few will have the courage and resolve to reach its end. Another theme is self-reliance and direct connection to the divine: the Master in Liber Tzaddi does not offer a conventional religion or fellowship, but rather urges the aspirant to seek the “Star” (divine light) within themselves and reject false gurus or fears. In this sense, the book encapsulates a strong Thelemic ethos: “Every man and every woman is a star”, capable of their own path, and those who are kindred spirits will naturally find each other by their common light. Finally, there is a theme of reconciliation of opposites hidden in the title itself: Tzaddi (a fish-hook) suggests pulling something from the depths, indicating that the initiate must draw wisdom from the deep unconscious (the waters of Nuit) by the skill of the Hermetic art. The seeker is poised between two cosmic extremes, the zenith of the highest possibilities (“height”) and the nadir of the most primal depths (“depth”). In both realms, the only constant guide is the self. Crowley reminds us that no angel outside, no demon foreign, can truly carry your will or your burden; only you can. Only by embracing and reconciling both poles of transcendence and immanence can one attain true equilibrium. Standing “upright” with head in heaven and feet in hell is a vivid image of vertical integration, a single axis that spans all levels of consciousness. Crowley acknowledges individual bias: some aspirants lean toward lofty spiritual visions (Angel), others toward the tumult of passion (Demon). His remedy: each must develop the opposite pole: mystics ground themselves in embodied discipline; libertines cultivate contemplative depth. This method ensures that neither pole dominates, producing dynamic balance rather than a static compromise. The promise is that as the adept graduates in this art of balance, the guiding intelligence (the speaker of Liber Tzaddi) will accelerate their progress. This is a potent statement of Thelema’s emphasis on self-responsibility and the discovery of one’s True Will as an inner compass.

Style and Symbolism:Liber Tzaddi is composed in a prophetic, free-verse style reminiscent of biblical exhortations or The Book of the Law itself. It is not very long (a few pages) but rich in metaphor. The speaker often shifts from admonishing the reader to exalting the spiritual quest, which gives the text a passionate, almost sermonic rhythm. The subtitle “Hamus Hermeticus” directly portrays the image of a hook used by Hermes. This hints that the text itself is like bait, designed to snare the soul that is ready, while remaining unseen by those not meant to notice it. Liber Tzaddi was published around 1911 inThe Equinox I:6, alongside other Class A texts, indicating it came somewhat later than the 1907 explosion of holy books. Its style reflects Crowley’s mature understanding of how to speak to potential initiates: a mix of encouragement, challenge, and revelation. Readers often experience Liber Tzaddi as personally speaking to them – the “Master” voice feels intimate. The closing lines project both warning and warmth, leaving the aspirant with the sense that a genuine Master has extended a hand, but only the truly Will-full will dare to grasp it. In essence, Liber Tzaddi is Thelema’s clarion call to the seekers of the world: a short scripture that separates “the kings from the slaves” by the very reaction it evokes in the depths of one’s soul.

Liber Cheth vel Vallum Abiegni, sub Figura CLVI

Role in Thelema: Liber Cheth vel Vallum Abiegni serves as an instruction for one of the most profound ordeals on the Thelemic path: the crossing of the Abyss. Crowley described it as “a perfect account of the task of the Exempt Adept, considered under the symbols of a particular plane, not the intellectual.”. The Exempt Adept (7°=4□) is the grade of a master who stands on the threshold of the Abyss, the great gulf between the human reason and the supernal consciousness. Liber Cheth is essentially the guidebook for the soul that is about to surrender everything and leap into the unknown. Its role is thus pivotal for those who approach the transition from Adept (in Tiphereth) to the sublime state of Master of the Temple (in Binah). The title is the Hebrew letter Chėth (ח), which corresponds to the Tarot trump The Chariot, a card Crowley associated with the path of Babalon and the Graal. Fittingly, the text’s role is to unveil the Mystery of Babalon, the Great Mother, as it relates to the Adept’s final surrender.

Major Themes: The dominant theme is Self-Sacrifice in the Cup of Babalon. Throughout Liber Cheth, the Adept’s ultimate task is allegorized in sexual and alchemical terms: the Adept (as the microcosmic “Beast”) must willingly “pour every drop of his blood into the Graal of the Scarlet Woman.” This symbolic act means yielding all of one’s ego, energy, and attainments — the “blood” being the life essence — into the Cup of Babalon, the divine receptacle. By doing so, the Adept is annihilated in personality and is reborn as a Master of the Temple, whose consciousness is merged with the infinite (Babalon being an aspect of the infinite divine mother). Another key theme is Erotic Mysticism: the text is suffused with explicit sexual allegory, equating the soul’s union with God with the tantric union of lover and beloved. It speaks of the “wine” of her fornications, the abandonment to the “embraces” of Our Lady. This is sexual magick veiled in symbolism, as Crowley’s note points out – the sexual act here is a sacrament, representing the creative/destructive force that propels the soul to Godhead. There is also the theme of Fear and Courage: the “wall of Abiegnius” in the title implies a fortification or barrier at the edge of the Abyss. The Adept must overcome the fear of loss and step beyond this protective wall. Abiegnus is a mythical secret Holy Mountain in older Rosicrucian lore, and by calling it a wall, Crowley implies the initiate must climb over the last boundary of the human domain into the starry city of Babalon beyond. Lastly, a theme of Universal Love appears paradoxically: in losing his finite self, the Adept becomes one with the All, typified by Babalon who “drinketh up the blood of the saints” and in whom all dichotomies are resolved.

Style and Symbolism:Liber CLVI is written in a highly charged, symbolic prose that is at once rapturous and foreboding. The style can be disorienting; it shifts between exalted praise of the divine feminine and stark commands to the Adept, making it clear that the most sacred spiritual act is intertwined with the most physical act of love. The Scarlet Woman Babalon is the central symbol: she is the “Mother of Abominations” from the Book of Revelation, reinterpreted in Thelema as the initiatrix who receives the aspirant’s ego-sacrifice. The number 156 is the value of BABALON in Hebrew gematria, linking the very number of the book to its goddess-theme. Cheth (ח), the letter, means “enclosure” or “fence”, appropriate to the idea of a walled sanctuary (or a graal as a container). The Chariot card (Atu VII) imagery resonates through the text: in Crowley’s tarot, the Chariot carries the Holy Grail with Babalon embodied therein, and the charioteer is the conquering hero who will offer himself into that cup. Received in 1911 and published in Equinox I:6, Liber Cheth reflects Crowley’s own intimate grappling with the Babalon mystique during that period. It stands as perhaps the most intense and demanding of the Class A texts: a direct dare to the advanced aspirant to “yield up thy self” utterly. For the reader, even if far from the Abyss, Liber 156 serves to clarify the stakes of the spiritual journey – nothing short of total sacrifice and divine union, vividly portrayed in the passionate symbolic language of the Scarlet Woman and her immortal wine.

Liber A’ash vel Capricorni Pneumatici, sub Figura CCCLXX

Role in Thelema: Liber A’ash vel Capricorni Pneumatici reveals “the true secret of all practical magick”, albeit in a heavily veiled form. In the Thelemic curriculum, it is an advanced treatise given to adept practitioners (it was published in Equinox I:6, alongside other higher-degree instructions). The role of Liber A’ash is to communicate the nature of the creative magical force in humanity and how to effectively awaken and wield it. Put simply, it is Crowley’s cryptic exposition of sex magick and the kundalini force, articulated in symbolic language so as to hide its secrets from the profane. The title includes Capricorni Pneumatici (“of the Goat of Spirit”), hinting at the astrological sign Capricorn and the goat symbolism (associated with Pan and Baphomet) as keys to the type of power being discussed. Thus, Liber 370 serves as a guide to the harnessing of the will using the most vital energy available to the magician – the sexual-spiritual energy – all under the cloak of myth and metaphor.

Major Themes: The overarching theme is the generation and use of the magical will (creative force). The text analyses the “nature of the creative magical force in man” and gives instructions (though couched as paradoxes and allusions) on how to awaken it, how to use it, and the objectives thereby to be attained. This creative force is essentially sexual energy – the power of Pan (fertility, frenzy) in its spiritualised form. A major theme is therefore Sex Magick, presented through symbols of goats, satyrs, gods and wine. The formula of “Issue and Withdrawal” appears, akin to the tantric idea of controlled expenditure of sexual force and its transmutation. The text encourages breaking down conventional morality and embracing the sacrament of the flesh as a means to spiritual ecstasy. Another theme is Illusion and Enlightenment: Liber A’ash deliberately uses absurd and blasphemous imagery to shock the mind out of its ruts. It extols both debauchery and sanctity in the same breath to show that All is One in the realm of true understanding. There is also a theme of Dissolution of the ego in Dionysian ecstasy – symbolised by the goat-god’s orgiastic rites – leading to union with the All-Father (that is, the universal creative spirit). In essence, the work promotes a form of the Left-Hand Path sacrament: using what is ordinarily seen as base or taboo (sexuality, intoxication) as the fuel for enlightenment.

Style and Symbolism:Liber A’ash is written in an outrageous, riddling style. It is composed of 61 verses of wildly varying length and tone. Crowley employs satire, shock, and holy nonsense to veil deep truths. On first read, the text can seem like blasphemous gibberish with bizarre alchemical wordplay and sudden intrusions of pious prayer. This deliberate confusion is a technique: only those with the intuition (or guidance) to parse the symbols will get the message, which protects the “secret of all magick” from the uninitiated. The symbolism is rich: Capricorn is the goat that rules the knees and the generative power; its planetary ruler Saturn relates to hidden wisdom and also limitation, reflecting the need for discipline in the practice. The goat also connects to Baphomet, the composite deity representing the unity of opposites (male/female, animal/divine) in occult lore – a perfect emblem for the kind of power Liber A’ash discusses. The term “Pneumatici” (“of the spirit or air”) juxtaposes the earthy goat with the airy/spiritual, again highlighting the union of opposites. Crowley’s use of language in this book is notably playful and syncretic: he mixes Qabalistic Hebrew terms, references to Christianity (in sarcastic tones), and classical pagan imagery. For example, one verse might sound like a debauched song to Pan, and the next is a profound zen koan. The effect on the reader is to break down rigid moral or logical structures, which is exactly the internal work needed to free the serpent power (kundalini) at the base of the spine. The adept who unravels Liber A’ash will come to understand how the ecstasy of Saturnalian rites can be harnessed for the Great Work. In Thelemic study, this text is often appreciated for its poetic madness and as a reminder that humour and holiness are not opposites – indeed, the union of laughter and worship herein points to a state beyond conventional dualities, wherein lies the supreme secret of doing one’s Will.

Liber DCCCXIII vel ARARITA, sub Figura DLXX

Role in Thelema: Liber DCCCXIII vel ARARITA is one of the most abstruse and exalted of the Holy Books. It is described as “an account of the Hexagram and the method of reducing it to the Unity, and Beyond”. In the A∴A∴, Crowley assigned it to the grade of Philosophus (4°=7□), calling it “the foundation of the highest practical Qabalah.”. Its role is to provide a blueprint for advanced mystical attainment, specifically the attainment of Unity with the All through a complex Qabalistic and magical formula. The word ARARITA is a notariqon (acronym) from a Hebrew phrase meaning “One is His Beginning: One is His Individuality: His Permutation is One.” This seven-letter word encapsulates the entire thesis of the work: that from unity everything proceeds and to unity all must return. Thus, Liber 813 serves as a meditative thesis on the nature of reality and the Great Work, written in a style to guide the adept’s consciousness through progressive states of unification.

Major Themes: The primary theme is Unity achieved through the resolution of all opposites. The text examines the Hexagram (the six-pointed star of macrocosm and microcosm) as the symbol of manifest existence with all its dualities, and instructs the magician in dissolving that sixfold complexity back into the One (the centre of the star). Each chapter of Liber 813 corresponds to one of the seven letters of that word, and each elaborates a stage in this initiatory process. Themes of transcendence recur as the aspirant is led to identify every phenomenon, every god, every demon, every thought with the One Reality. Another theme is the formula of the numbers 6 and 7: the Hexagram (6) plus the Unity (1) gives 7, which is ARARITA’s letters. This is mirrored in the structure of the book with its seven chapters. The sub-theme is that by comprehending the interplay of the six (perhaps the classical planets or the six Sephiroth of the microcosm below the Abyss) and then assimilating them, one attains the seventh principle, which is beyond (the divine or the septenary unity). There’s also a strong theme of self-annihilation in the sense of transcending the ego: one must recognise “that which is below is as that which is above” and thus the self and the universe are identical, leading to the obliteration of the illusion of separateness. Additionally, ARARITA deals with sacred geometry and word mysticism since it’s laced with equations of divine names and elaborate wordplay to demonstrate how diverse concepts equal each other in the One; for instance, it might equate different deities or symbols through numerology or Qabalistic manipulation, underscoring unity.

Style and Symbolism: Liber 813 is composed in a series of numbered paragraphs that read like a cross between a mathematical proof and a hymn. The style is declarative, abstract, and grandiose. Each statement builds upon the previous to form a kind of logical-yet-mystical progression. Yet, the content is so lofty and symbolic that it’s more like poetry of ideas than a practical manual. Symbols central to ARARITA include the Hexagram (often in the form of “Uniting the Hexagram” as a ritual or internal act), the Rosy Cross (implied by union of 5 and 6, and the concept of the universal solvent love that unites all), various gods from multiple pantheons (indicating that all gods are facets of the one God), and technical terms from mysticism (Neschamah, etc., referring to parts of the soul). Crowley notably says this book “describes in magical language a very secret process of Initiation.” Indeed, those familiar with Golden Dawn or A∴A∴ practices might recognise in ARARITA the sublimation of certain advanced rituals (like the hexagram rituals or the inner alchemy of uniting opposite forces in the soul). The text was received in late 1907, likely during the same creative period as Liber LXV, and it bears the mark of intense concentration. Reading ARARITA is often compared to chanting a litany, since its repetitive, formulaic cadence can induce a trancelike understanding if approached as meditation. For the serious student, working through Liber 813 is a mental and spiritual discipline: one must unpack dense layers of Qabalistic correspondences and paradoxes to glean the intended transformational insight. When that insight comes, the adept perceives the Unity that underlies the apparent complexity of the universe, which is precisely the enlightenment ARARITA is meant to convey. We can rightly surmise that his text is the capstone of the Holy Books’ curriculum in many ways: a succinct but arcane map of the final steps to Union with the All, written in a code that only patience and purity of aspiration can fully decode.

The Way Ahead: Living the Holy Books

The Holy Books of Thelema, with their cryptic verses and exalted imagery, invite the seeker into a world of mystery and gnosis. For the newcomer, they can seem daunting, filled with strange names, prophetic declarations, and esoteric symbols. Yet, as we have seen, behind their veil lies a coherent mystical journey: the Class A texts were born in ecstatic revelation and meant to awaken a similar flame of spiritual aspiration in those who engage with them. Crowley, despite his often flamboyant and controversial persona, speaks in these Holy Books with the voice of intimate spiritual experience – a voice by turns gentle, fierce, rapturous, and inscrutable.

In the broader context of the world’s mystical literature, Thelema’s Holy Books stand alongside works like the Bhagavad Gita, the Tao Te Ching, or the mystical poetry of Rumi, in that they are scriptures intended to transform the reader’s consciousness. Their approach is syncretic and modern, yet rooted in ages-old traditions: the Law of Thelema echoes classical ideals of finding one’s true purpose and aligning with the cosmic order, even as it breaks old dogmas to forge a new spiritual identity for the modern age. By integrating elements of Egyptian paganism, Hermetic Qabalah, Eastern philosophy, and Western occultism, the Holy Books create a unique array of symbols. A newcomer might not grasp every reference at first (and need not!), but can certainly feel the atmosphere of the sublime and the revolutionary that these texts exude.

Approaching these books with a sympathetic eye, one discovers the richness and transformative potential that Thelema offers. The figure of Babalon encourages us to find holiness in what is earthly and to embrace the All without fear. The Holy Guardian Angel doctrine reminds us that we carry a spark of divinity – a personal guide – and that the universe is not devoid of meaning or help. The Crossing of the Abyss teaches the paradox that by losing oneself, one finds the All; by dying to the ego, one is reborn to a higher life. These are universal mystical truths, clothed in the daring language of the New Aeon.

For those new to Thelema, the Holy Books are best read not as dogma, but as invitations to experience. One is encouraged to “interpret them each for oneself” – to meditate on the verses and see what insights arise, to perhaps perform rituals or practices that Crowley recommended alongside study (like yoga, magical rituals, or invocations of the deities and angels mentioned). Over time, the symbolism begins to speak more clearly, and the aspirant finds that the journey described in these texts is mirroring changes in their own soul. In this way, the Holy Books of Thelema function as a living oracle and companion on the path. They carry the potent magical current of Thelema, a current that proclaims freedom, love, and personal discovery of the divine.

STARS & SNAKES IS OUT NOW

I’m pleased to announce something new: the release of Stars & Snakes: A Thelemite’s Field Notes—a collected anthology of these very writings, gathered together in one volume under my own independent Chnoubis Imprint.

This is one of those topics where I get pedantic. “Holy Books,” the numberical order of the texts, which ones are included, the classification system itself (that it even applies outside the A∴A∴ and/or O.T.O., or that Class A is a “scriptural core” of Thelema in the first place when that is categorically untrue in several cases), the insistence of broadening the political Tunis Comment from Liber AL to other Class A texts, the inconsistencies of Crowley’s use of Class A, etc. I could go on because this was such an in-depth dive for me in the canonization study.

But even here, you’ve conflated “Holy Book” with Class A—which still assumes Class A to mean anything outside of A∴A∴/O.T.O.—and then only included 11 of the 13 Class A texts, of which only 5 did Crowley ever consider to be core texts in the first place. (The “Holy Books of Thelema” is entirely a McMurtry (though some say Breeze) verisimilitude.)

That said, when it comes to the actual breakdowns, you have literally written out the format that I’ve always wanted to see someone do for a study version of the Holy Books: Intro—Theme—Style. I love it! It’s brilliant. I remain absolutely convinced that a study/student version of the Holy Books (and then some) would be invaluable. But it would take more than just some additional footnotes. It would take a commission of some sort to get it right. And we still have way too much crap in our community for that to be successful. Until then, breakdowns like this are absolutely invaluable! You continue to do our community such a service with such things.

Thank you for this compendium of knowledge, Marco. It is already propelling me into further study and a resurfaced enthusiasm, after a very dry and very busy period. Extremely helpful.